Hi from Tallinn,

Journalists don’t usually talk about their own profession. We wouldn’t like to do it today, but we’ve been forced into this situation.

Two weeks ago, police paid a visit to the newsroom of Domani, European Focus’ partner in Italy. The aim of the move seems to have been to scare off the reporters from investigating certain topics that are uncomfortable to the government.

This is part of a pattern. Press freedom and the safety of reporters is often under attack, even in countries that have a functioning democracy. Just take a look at how the BBC tried to muzzle the social media comments by one of its sports presenters, Gary Lineker. But no democracy can function without a truly free media.

Even here in Estonia – which ranked number four in the 2022 press freedom index – reporters suffer from abuse. Last year prosecutors tried to fine journalists unless they received approval from prosecutors to publish specific stories.

I hope that our today’s selection offers a fine balance between drawing attention to the problems, but also to the press’s responsibilities.

Holger Roonemaa, this week’s Editor-in-Chief

French journalist Olivier Dubois, who works with our newspaper Libération, was released on 20 March after 711 long days in captivity.

711 days since he was kidnapped by the Support Group for Islam and Muslims (JNIM, in Arabic) while he was reporting from Gao, in northern Mali.

711 days that he was held hostage somewhere in the Sahel region. 711 days that he was the only known French hostage in the world. 711 days that this father of two missed his family, his friends, and his colleagues. 711 days that journalism missed him.

711 days of silence, fear and hope. 711 days too many.

On 3 March, the police arrived at Domani’s newsroom, with the unusual aim of seizing an article that related to Claudio Durigon, an undersecretary in PM Giorgia Meloni’s government.

The authors, Giovanni Tizian and Nello Trocchia, are authoritative reporters who cover the collusion between politics and organized crime. They are both under state police protection. One would expect the Italian authorities to safeguard their work. They came to seize it, instead.

“It was so surreal,” says Mattia Ferraresi, managing editor of Domani, where I also work as a reporter. He had to print the article for the police. Durigon had sued us because of that article, which he didn’t even attach to his lawsuit. The piece was publicly available online.

“There was no need for the raid, this is intimidation!” says Ricardo Gutiérrez, general secretary of the European Federation of Journalists. This is the second alert that Gutiérrez has written related to Domani in a few months: last autumn Giorgia Meloni sued my editor-in-chief Stefano Feltri and my colleague Emiliano Fittipaldi.

These are “governmental SLAPPs” (Strategic lawsuits against public participation), with an aim to silence journalists. “Every time we write about Durigon, he sues us,” Trocchia says. “He has done this eight times.”

When the police came, Tizian was on his way to the newsroom. Trocchia informed his colleague by phone: “Come, the police are here!” Tizian’s first thought was to protect sources: “Don’t let them touch our computers!”

Following the raid, a coalition of media freedom organisations launched an alert at a European level. Progressive groups in the European Parliament (S&D, Greens, Left, Renew) expressed their support, and MEP Sophie in’t Veld asked questions to the EU Commission about the case.

On 15 March, Rome’s attorney stated that seizing the article was improper and invalid. This made me realise how important it was to have a huge European mobilisation to condemn this act.

A moment after this picture was taken, the woman held in an embrace in the centre broke into tears. Her legs gave way, and she collapsed, swallowed by grief.

This is Alina Mykhailova, a fiancé of the Ukrainian military Dmytro Kotsyubailo. Known by the call sign Da Vinci, he was one of the most talented and respected young officers in the army. Recently, he was killed in a battle near Bakhmut.

At his funeral on 10 March, the President of Ukraine, the Commander-in-Chief, the Minister of Defence and thousands of other Ukrainians stood down on one knee ― a mark of the highest respect.

Photographers kept taking pictures, and images of the heartbroken woman went viral. This caused a debate in Ukrainian society: how ethical is the broadcasting of psychically and emotionally challenging moments of someone in such a position as Alina?

One side says that Alina is a victim, and her right for privacy is sacred. The other side, which often includes journalists, insists this is war, and such expressions of grief are a significant part of it. To show this to the world is just and even necessary.

“I watch this ― and in my guts I feel that Ukrainians exist and I’m among them. The woman in the photo turns all of us into a living, pulsating social body,” wrote art curator Olena Chervonyk in a widely read article.

“It’s possible to nurture your Ukrainianness by other means. A person has the right to life and to death, which has to be respected even in such circumstances,” replied lawyer Larysa Denysenko. “This is not my pain, not my trauma, not my private space.”

Alina Mykhailova is also a politician and a soldier, and probably has her own thoughts on this issue. But she has not yet shared them, as she has been spending long hours every day at Dmytro’s grave.

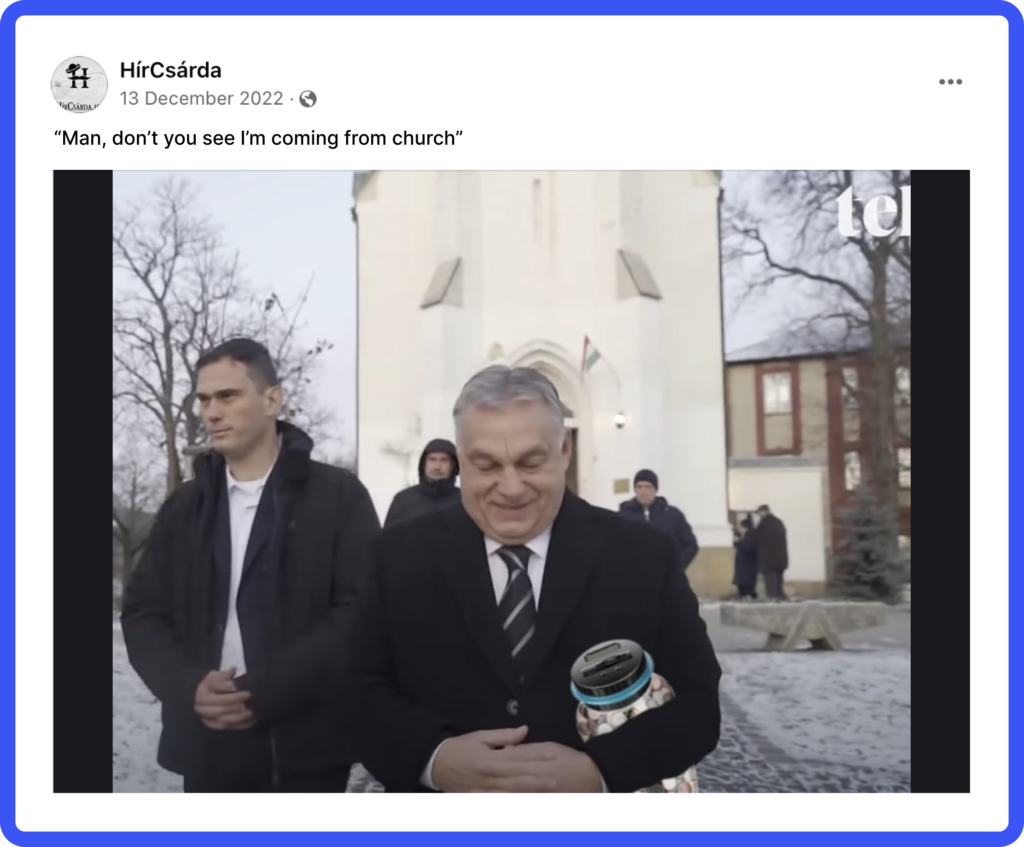

What can a journalist do when a prime minister hasn’t given an interview to the independent press in 13 years? Approach him in front of a church. And what does a prime minister say when he sees such a reporter moving up to him?

“Man, don’t you see I’m coming from church?”

This was the answer by Hungarian premier Viktor Orbán to a well-known journalist, which became an instant meme, mocking everything from corruption to press freedom.

Approaching someone after mass may seem rude, but Hungarian journalists have no other option. Being excluded from press conferences and not receiving replies is everyday reality for reporters who are not aligned with the ruling party, Fidesz. Some have been targeted with the surveillance software Pegasus.

As to why this is necessary, the political director of the prime minister once argued: the one who controls the media is the one who controls the country. But there is one thing they cannot control: jokes.

Although German journalists are regularly insulted, mainly by right-wing activists, for being “state media”, most people here have no idea how a state media really functions.

Three years ago, I spent two months working for a genuine example of such a press: Vaticannews – an online portal owned by the Vatican that disseminates information about the Pope’s activities, the Vatican, and Catholic teaching worldwide.

As a journalism student looking for an internship, I thought Vaticannews would be an interesting place to learn my craft. It was certainly interesting. However, I didn’t learn so much about journalistic techniques, but more about the boundaries which journalists can face.

Not surprisingly, my own report into the workings of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith did not get very far. This is the successor authority to the Inquisition, responsible for keeping Catholic doctrine pure. A background discussion with one priest working for the congregation did take place, but led to little actual information.

When afterwards, I sent a question about a pending case concerning the verification of an apparition of the Virgin Mary, I received a rebuke, more or less indicating me that I — as an intern of a Vatican media — should have been instructed by my colleagues not to report on such controversial issues.

What I found surprising was that there were tangible diplomatic interests of the Holy See that we had to take into account in our reporting. Human rights violations in China? Difficult.

The Pope has been trying to negotiate with China for best protection for Catholics in China who are recognised as being members of a sort of “official” Church by the Chinese state.

In order not to jeopardise these negotiations, the bosses at the press told us to avoid criticism of China. This seemed to me to be grounded in a rather worldly consideration.

Back in Germany, I felt relieved that finally again, I was allowed to devote myself to the sacred goals of critical journalism.

Thanks for reading the 24th edition of European Focus,

I am afraid that press freedom is something that many of us take for granted. We won’t notice how vital this liberty is until we’ve lost it. And then it is usually too late to repair.

If you care about these issues, please spread the word, and when you notice next attempts to restrict press freedom, please draw attention to it. This helps us.

See you next Wednesday!

Holger Roonemaa