Hi from Budapest,

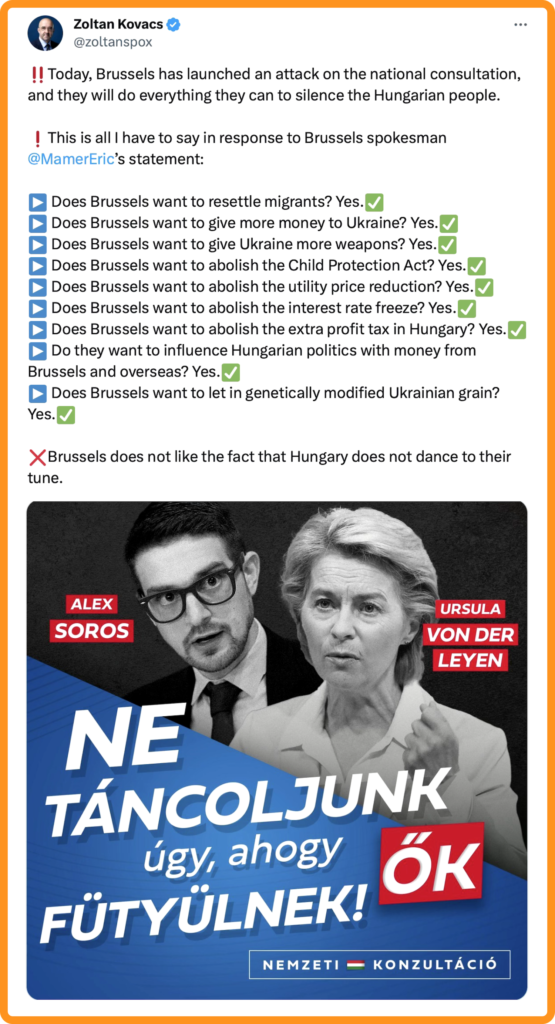

The streets of my city are a curious sight to see. Families are doing their Christmas shopping under the watchful eye of European Commission president Ursula von der Leyen and Alexander Soros, son of Hungarian-born billionaire, George Soros, portrayed as enemies of the state on blue billboards financed by the Hungarian government.

The posters are part of a new campaign by Viktor Orbán, who has made “protecting national sovereignty” a new slogan ahead of the European Parliamentary elections in 2024. While the Hungarian prime minister considers Brussels and Washington as potential threats, other European countries would say the same of Russia – whose leader Orbán recently shook hands with.

The premier is right about one thing: in the wake of recent world events, national sovereignty is something we all must talk about. What does sovereignty actually mean? Does it refer to resisting interference from a foreign country, or protecting national interests? And can we talk about sovereignty at all in the context of the European Union?

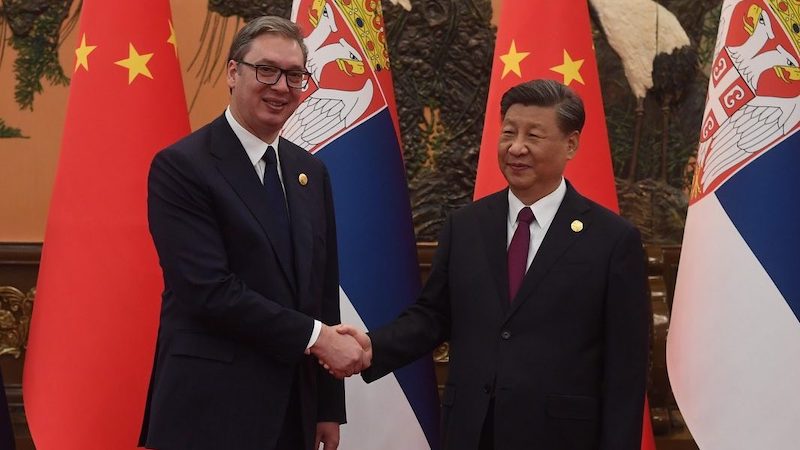

From Russian influence in France and Estonia, to China’s strong business ties to Serbia, this is what we plan to uncover in this week’s newsletter.

Viktória Serdült, this week’s Editor-in-Chief

Nicolas Quénel is a specialist in the intelligence services and disinformation wars. He has recently written Allo Paris? Ici Moscou, Plongée au cœur de la guerre de l’information (Hello, Paris? This is Moscow. A dive into the heart of the information war).

Is France particularly targeted by Russian influence operations?

Along with Germany, France is one of the EU member states most affected [by Russian influence ops], and has been for a long time. French authorities have been confoundingly naive in their dealings with Moscow. In 2006, President Jacques Chirac decorated Putin with the Grand Cross of the Legion of Honor [France’s highest distinction], and in 2011 President Nicolas Sarkozy signed a contract to deliver helicopter carriers to Russia while the Russian army was occupying northern Georgia. In 2017, the first thing Macron did once he was elected was to receive Putin at Versailles. Two years later, in a speech in France alongside the Russian president, he said that Russia was “profoundly European” and a “great Enlightenment power”. The obsession was to normalise relations with Moscow.

How do you explain the extent of Russian influence in France?

There are several historical reasons. The anti-Americanism of the French elite played a role, as did the presence of a long-standing and powerful French Communist party and the existence of a press that emphasised opinion articles and was therefore more permeable to Russian discourse.

But just recently, France was the subject of an interference operation probably directed by Russia…

That’s right, a Moldovan couple were paid to paint Stars of David on the walls of Paris to stir up trouble in French society, and Russian bot networks relayed the images. It was a low-cost operation, but it worked. The media covered it extensively before it became clear that it was a remote-controlled operation from abroad. Intelligence services are noticing a return to these modes of operation, reminiscent of those used during the Cold War. In 1960, the KGB did exactly the same thing in West Germany, painting swastikas on walls to suggest that Nazism was returning to Germany and to undermine Western confidence in their partner.

A party needs to surpass five percent of the popular vote to be elected to the Estonian parliament, but a threshold of two percent is enough to qualify for state funding. This is the proportion the pro-Russian Left Party achieved in elections this year, after a campaign by their candidate Aivo Peterson.

The political figure became known for his trips to the Russian-occupied Donbass region and his blatantly pro-Kremlin rhetoric. It didn’t take long for Estonian authorities to discover that he has received instructions from Russia.

Peterson is now in jail awaiting trial, accused of treason. Despite this, the Left Party will continue to receive money from Estonian taxpayers.

“We have to, you know, live even before joining the European Union, and we have to think about our country, our children and our future,” Serbian president Aleksandar Vucic told media in Beijing in mid-October prior to his ministers signing a free trade agreement between the two countries.

Vucic’s statement was a reaction to EU Commission spokesperson Peter Stano, who said Serbia would have to withdraw from all bilateral agreements with third parties on the day it joins the EU.

According to data published by Serbia’s Statistical Office, China was Serbia’s second-largest import partner between January and September 2023. The report, however, also notes that Serbia’s corresponding exports are not high, and the country’s biggest trade deficit is with China.

This agreement is a step forward in deepening the economic relations between the two countries.

China has been financially present in Serbia since before Vucic’s Serbian Progressive Party came to power, but this relationship deepened in the last couple of years. It helped Serbian authorities to “keep jobs”, such as in the Smederevo Ironworks, which was bought by China’s Hesteel Group (HBIS) in 2016, and to build kilometers of highways, which leaders have declared is a great success and a sign of progress.

At the same time, these projects did not conform to the country’s legal system, and were a direct deal between the state and its Chinese partners. In practice, this meant that Serbia did not consider other offers. The subcontractors on these projects are domestic companies, but, in some cases, those were close to the ruling elite.

Serbian institutions never reacted to serious allegations of violation of workers’ rights in Chinese companies and problems with pollution.

According to an analysis by BIRN, in 2021 there were at least 61 projects in various stages of completion in Serbia that had been or were being implemented by or in cooperation with Chinese entities over a decade, with a value of at least 18.7 billion euros.

Sovereignty is the new buzzword of the Hungarian government. Not only did they submit a so-called sovereignty protection bill to parliament, but they also launched a national consultation and a poster campaign.

The bill would establish an authority to detect and monitor any risks of political interference. It would also punish foreign funding of parties or groups standing for election with up to three years in prison.

The poster campaign gives the impression that foreign interference in Hungary partly comes from the European institutions, and shows Alex Soros, son of Hungarian-born billionaire, George Soros, behind European decisions. Similar billboards against George Soros and former European Commission president Jean-Claude Juncker have appeared before. What’s ironic is that the Hungarian government has praised Juncker’s successor, Ursula von der Leyen.

Times have changed, believes the populist Fidesz leadership, and the EU has become a target. The message of Zoltán Kovács, international spokesman of the government is: Hungary does not dance to their tune.

“Go to Berlin!” shouted Law and Justice (PiS) MPs when Donald Tusk, the future prime minister of Poland, appeared in the Polish parliament this summer. The narrative that the opposition leader was “in the pocket of Brussels” and pursuing anti-Polish interests permeated the election campaign in October 2023.

The PiS propaganda suggested that the opposition’s win would result in Poland losing its sovereignty. The Poles, strongly in favour of EU membership, didn’t buy it. Moreover, the European Commission has already announced it will unblock billions for Poland from its Recovery and Resilience Funds this year.

This money had been frozen because the nationalist-conservative Law and Justice (PiS) government would not withdraw its widely criticised justice reform. In Tusk’s case, his visit to Brussels and announcement that he would shelve this reform were enough. Tusk, while not yet prime minister, already has a major success to his credit, that neither the PiS nor the outgoing government of Mateusz Morawiecki can boast about.

The PiS government’s anti-EU policy was primarily intended to dampen criticism of Brussels at home because of the government’s authoritarian inclinations. Over the past years, Morawiecki’s government took a drastic turn to the right and Poland became a Trojan horse of extremist ideas in the EU. Neither Warsaw nor the Poles have benefited in any tangible way from this.

However, by stirring up conflict between the European Union and Poland, the Morawiecki government was fostering the interests of the Russians, who were seeking to weaken the bloc. Signs are multiplying among opposition figures and journalists that some PiS politicians were aware of this, and may have openly favoured Russia. These links should be investigated by the politicians who are about to take power very soon.

Thanks for reading the 54th edition of European Focus,

The concept of sovereignty has had varying definitions, and diverse applications throughout history. Though we never expected to solve the puzzle, we certainly hope we gave you some food for thought before the Christmas season begins.

And if we did, feel free to share them with us at info@europeanfocus.eu.

See you next Wednesday!

Viktória Serdült