Hi from Budapest,

Though born and raised in the Hungarian capital, I come from an extended family of agricultural workers. Every summer, I would spend weeks at my grandparents’ home in eastern Hungary, marvelling at the sight of tractors ploughing, tilling and planting.

I can still hear my grandma’s words echoing in my ears: “See? That is where our food comes from.”

Little did I know that a few decades later, tractors would symbolise something quite different across the continent: discontent. From France to Romania, farmers are blocking roads to protest against their living and working conditions, and the threat they see in the European Union’s common agricultural policy. Before the upcoming European Parliamentary elections, political parties are rallying behind them.

While farmers face similar difficulties in every country, the real driving force behind their protests may differ. Is it just discontent with the EU? A spat with their government? Market inequalities? Or all of the above? This is exactly what my colleagues from different corners of the continent explain in this week’s newsletter.

Viktória Serdült, this week’s Editor-in-Chief

The scenes were unruly: earlier this month, demonstrators heckled German economic affairs minister Robert Habeck as he returned by ferry from the island of Hooge off the country’s northern coast, and prevented him from disembarking. Hundreds turned out to voice their grievances, and while the situation did not escalate, it set the scene for a month of intense protests.

Farmers across Germany are angry over government plans to cut their tax breaks, particularly on diesel fuel and vehicle registrations. But while most of the protests, which began in December last year, have been peaceful, some have crossed a line. In cities such as Kassel, Stuttgart and Berlin, a traffic light, symbolising the ruling three-party coalition, was seen hanging from a gallows.

Linking both these incidents is a group known as ‘Landvolk’ – a movement originally founded in the 1920s in northern Germany in response to the agricultural crisis of the time. Their activism ranged from tax boycotts to planting explosives, and helped pave the way for the Nazis.

Today, the Landvolk is back in fashion in some circles. Its flag has been waved at the growing number of agricultural protests.

Far-right parties such as the AfD are trying to capitalise on the farmers’ discontent. They are joining the protests and expressing solidarity. Meanwhile, the German Farmers’ Association has distanced itself from “idiots with fantasies of overthrowing the government”.

For now, experts and authorities see no serious signs of a radicalised farmers’ movement. But even if the extremists remain at the fringe, the situation appears more dire in parts of the German east. In recent years, several villages have been taken over by so-called “ethnic settlers”, who, under the guise of organic farming and nature conservation, propagate the superiority of the German race, while rejecting democratic society. With three eastern German states holding elections this year, vigilance is key.

Farmers in France work around 55 hours a week, compared with 37 hours for the “average” worker. No other profession labours as hard as them.

Their working and living conditions have deteriorated in recent years. They face falling incomes, high debt, rising production costs, farm closures and a lack of free time.

In an attempt to win concessions from the government, farmers have been blocking several roads around Paris since Monday. Among other measures, they are hoping for a law prohibiting the purchase of agricultural products for less than cost price. But by blocking roads, farmers also risk losing the support of the public.

For almost a year, Ukraine’s Western border checkpoints haven’t offered a clear passage to the EU: from time to time, they are taken over by protesters.

Firstly, these were Polish farmers who blocked control points between the two countries during last April.

In November, truckers in Poland built a blockade that grew longer and larger, then the farmers joined them. For weeks they only allowed humanitarian cargo and a limited number of commercial trucks to pass through to Ukraine, causing significant delays to supplies for the Ukrainian military. This resulted in about $1.5 billion in losses for the Ukrainian economy, just in November-December.

Both farmers and truckers demanded stronger regulation on their Ukrainian counterparts. At the start of Russia’s full-scale invasion, these groups had de facto equal rights with the EU truckers. Ukraine’s neighbours felt this strongly. They feared price-dumping for goods and services. Cheap grain and logistics disrupted their markets. For example, due to an influx of Ukrainian grain, wheat on a Polish agricultural exchange in 2023 was sold for half as much as in 2021.

Emotions of Polish farmers are best described by the name of their initiative group – “Deceived village”. Similar feelings were expressed by their Romanian, Slovak and Hungarian colleagues. In the last three months, all these countries’ border crossing points with Ukraine were blockaded for hours ― or weeks.

This is the beginning of the story. As Kyiv is already in accession talks with Brussels, the Ukrainian market will someday merge with the EU. And Ukraine is an agricultural powerhouse. Wheat is just one item. For corn, barley or rapeseed, it’s among the top world exporters. The country also produces tomatoes, honey and poultry, so there are reasons for EU farmers to worry.

An intricate process of aligning two economies is required. Otherwise there will be more protests ― even louder ones.

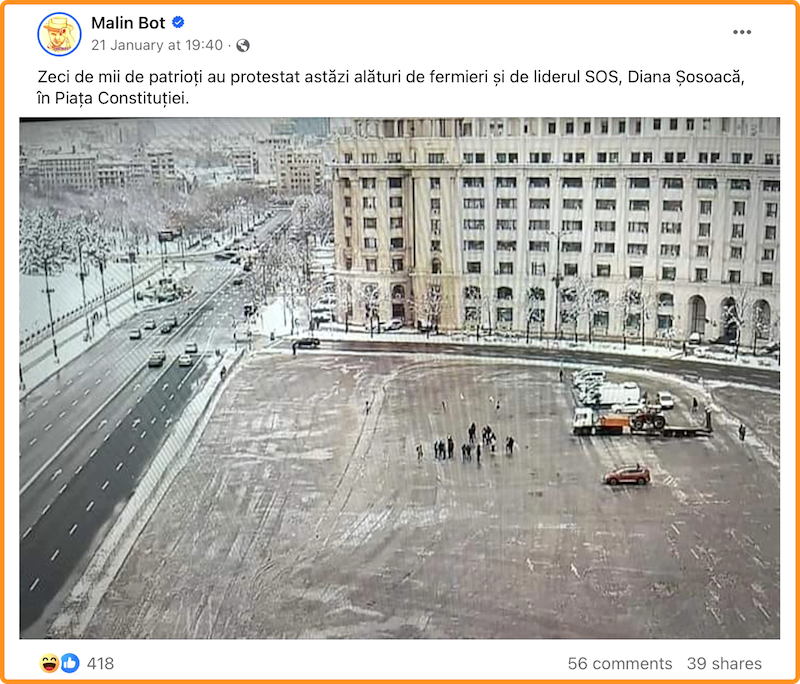

One of Romania’s best-known scandal-mongers, far-right senator Diana Soșoaca, was stranded in Bucharest’s Constitution Square after organising a demonstration to support the country’s farmers.

Romanian farmers have been protesting across the country since 10 January, demanding control of Ukrainian grain transits through Romania. In addition, they called on the government to maintain the reduction of excise duty on diesel used in agriculture. They also protested against the authorities’ tightening of nature conservation standards for agriculture.

The far-right parties AUR and Soșoaca’s SOS RO wanted to join the protesters. However, the farmers distanced themselves from both. Though Sosoaca’s party received a permit for a march of 5,000 people, 100 tractors and 100 tractor-trailers in the capital, it was all in vain. The farmers preferred to demonstrate in the suburbs of Bucharest, in order to avoid association with the Romanian far-right

The caption beside the post above ironically mocks the situation: “Tens of thousands of patriots protested today alongside farmers and SOS leader Diana Sosoaca in Constitution Square”.

Farmers are protesting across Europe, and the far right is championing their cause. In reality, the protectionist narrative of the protestors clashes with the neoliberal economic agendas of some examples of the extreme right, explains Guillermo Fernández-Vázquez, author of ‘What to do with the extreme right in Europe. The case of the National Front’.

We are seeing widespread protests among farmers across Europe. How is the far right exploiting these protests?

Almost all European far-right groups are proposing what they call ‘protecting’ the sectors of the economy which they consider strategic from a national or purely electoral point of view. They complain that the EU imposes too many controls, which makes the primary sector uncompetitive in respect to third countries.

What is the situation in Spain?

In Spain it is quite striking: [far-right party] Vox, in its attempt to become the party of the farmers, is the one most publicly highlighting the demands of the agriculture sector, which complains about competition from North Africa. In the last elections, Vox electoral posters in the countryside, apart from the general slogan ‘Vote what matters’, there was another that said ‘Vota Vox, vota campo’ (Vote Vox, vote for the countryside). It was very obvious that Vox wanted to be identified as a party of the farmers. But this is a protectionist narrative that clashes with the liberal economic measures in their party programme.

How does this duality between protectionism and liberal economic measures clash?

The European radical right (with the exception of France), has put much more emphasis on cultural identity than on economy. The economy was an excuse to talk about their main problem: immigration. And this is still happening.

For example, in Castilla y León, where Vox holds the vice-presidency, on the one hand they publicise this protectionist discourse and at the same time they push for classically neoliberal measures in parliamentary votes, such as eliminating subsidies to employers and trade unions. In reality, it is a project that is still quite incoherent economically. It creates difficulties between the more clearly liberal wing and other discourses that sometimes emerge. There is a discordant polyphony.

Thanks for reading the 59th edition of European Focus,

When was the last time so many people rallied behind a single cause in Europe? Farmers’ protests across the continent have shown us what happens when people’s voices are not heard.

And while environmentally friendly methods of farming are not a choice, but an obligation, maybe now is the time to make decisions together with those whose lives are affected the most. After all, this is what the European Union stands for.

See you next Wednesday!

Viktória Serdült