Hi from Kyiv,

As I write this (on Tuesday), Ukraine is under the strongest missile attack since 24 February. With our colleagues on the ground, now all in shelters or the safest places in their flats, we monitor the news. There are live updates about power cuts in major Ukrainian cities: Kyiv, Kharkiv, Lviv…

“And you know what my mother just asked?” a colleague in Kyiv just wrote to me. “How long does it take to bake a Camembert?”

We all know that this winter won’t be easy. Maybe the Russian attacks will make our lives here unbearable, and some of the people in these chats will soon be writing from safer places.

Maybe there will be more stories like the ones in this issue: about the challenging integration of Ukrainains in west Europe, like Olha’s from Germany, and about the longing for return, like Daria’s from France.

But none of the people in my chat rooms have plans to leave Ukraine, not even today. Quite the opposite: millions of Ukrainians are now bulking on wood, coal, diesel generators, power banks ― whatever helps us maintain the lifestyle we are all defending now. Baked Camembert included.

Anton Semyzhenko, this week’s Editor-in-Chief

“You are living in a fairy tale,” a neighbor in the small German village where I fled from Ukraine in the spring told me. But beautiful scenery is not enough to calm someone living under constant stress.

My current house has more items than my apartment in Kyiv. The whole village helped me, by collecting kitchen utensils, furniture, and clothes. People even found a coffee machine when they heard that I liked coffee. I had almost everything.

But my integration was like a slow walk. I woke up around 4 a.m., checked if everything was okay with my friends and relatives in Kyiv, and then fell asleep until 9 a.m. when I started working. I had permanent internet access and didn’t need to hide in a damp basement. But the inner numbness of my life changed so quickly. The dissonance between the photos from Ukraine and the landscape outside my window kept me awake.

Of course, this was the first stage ― a rejection of the new reality, combined with an uncertain future. Having overcome the fear of speaking German, I began to communicate with locals more. When I started to understand how these people live, it became easier to overcome stereotypes.

Germany isn’t just a country with a strong social security system, and a place where nothing should ever distract people from planning their weekend entertainment, as some stereotypes suggest. It’s a very diverse place with its problems and divisions, rules and traditions.

I have accepted the new rules of life and broken down many barriers: linguistic, emotional, bureaucratic. Openness, gratitude for people, and activity helped it all go smoothly. But…each of our stories is much more complicated than any “fairy tale” we see in the lives of others or that they see us in.

Poland expects 500,000 Ukrainians to arrive in the coming months, fleeing winter, increasing Russian terror and a lack of access to water, electricity and heating.

There are more than a million Ukrainian refugees in Poland. Aid agencies predict the new arrivals will be different, and traumatized by the war. Feeding them could be a challenge. There are currently 80,000 refugees sheltering in aid centers, and many living in overcrowded housing.

In the first weeks of the war, Polish society gave massive support to refugees. Solidarity may again be needed as migration experts believe the state’s preparations are inadequate.

Daria remembers the night of 23 February as if it were yesterday. The 29-year-old film producer was sleeping in her spacious Kyiv apartment with the window open when sirens sounded. “I was annoyed because I thought it was a car alarm,” she says.

“I turned on my cell phone and my mother had posted a message on the family group in WhatsApp. ‘It’s started’, she said.” The first explosions struck the Ukrainian capital. “I was shocked, paralyzed. I took refuge in a shelter. I thought I would stay there for twenty minutes, but I spent two weeks without going outside,” adds Daria.

The Russian invasion triggered a trauma for her. “I started to feel very bad. I couldn’t sleep. I told myself that I had no choice but to leave.” On 18 March, Daria left Kyiv in a hurry with a small bag, “like a refugee”. Her destinations were Warsaw, then Geneva, then Paris. She had already studied cinema for five years in the French capital, and joined tens of thousands of Ukrainians who found refuge in France.

Daria put her bags down at a friend’s house, in the lively Buttes-Chaumont neighborhood.’For the first few days, she managed to rest a little. Her big blue eyes were tired from sleepless nights spent collecting money for the war effort or in the kitchens, where she prepared meals for Ukrainian soldiers.

But even in Paris, something seemed wrong. Despite her friends’ support, Daria felt alone in her struggle. “When I arrived, I found it hard to see people happy, to be in a country at peace when mine was at war,” she says. Daria tried by all means to inform the French about the situation in Ukraine.

She participated in all the demonstrations, organized solidarity dinners, and covered herself with fake blood to try to alert the population. She never went out without her Ukrainian flag, which she tied on her shoulders. “I recreated the atmosphere of wartime kitchens in the 10th arrondissement of Paris. [To raise money for the war effort] We prepared 1,000 meals for the locals, but sold only 50 of them. I was really disappointed. French people don’t understand that Ukrainians are fighting to protect the rest of Europe,” she says.

On 19 May, Daria made a radical decision: she returned to Ukraine, even if this possibly meant losing her life. She needed to find her friends, her family and be among those “who know what war is”. On her way back, where I joined her, her emotions changed from laughter to tears. On the train between Poland and Ukraine, she could no longer hold back her emotions: “It’s over, I’m going home,” she said, before bursting into tears. Her smile widened as she moved closer to home.

Now the country is chaotic. In most cities, anti-bombing sirens still wail several times a day. In Kyiv, it is possible to have brunch on the terrace of a trendy restaurant down the street from military funerals. But the young producer knows that she’s not alone. More than 2.5 million Ukrainians have returned home since the beginning of the Russian invasion. Six months later, Daria has no regrets. She tells me that she will stay in Ukraine “until the victory”.

“Every time it’s like the next level in a computer survival game. Now there is no electricity or water supply, frightened employees don’t come to work. Or they show up, but can’t stand the pressure,” writes Anna Zavertaylo, co-owner of the popular Honey cafes in Kyiv.

Since the Russian strikes on Ukraine’s critical infrastructure, which started on 10 October, there have been daily power cuts in Kyiv to save energy. Anna’s business is trying to adapt. When the power is out, the confectioners wear headlamps, so they can continue making desserts.

It’s the same in many places for eating out. The Ornament cafe, after the blackouts started, initially offered a limited selection of drinks from its menu, such as filter coffee, which can be brewed in advance and stored in a thermos.

Now, after purchasing a small gas stove, all drinks are available. Kha.food, which sells Kharkiv traditional square pizza, announces its opening hours daily on social networks. The Greek restaurant Chaika warns that when there is no electricity, visitors can enjoy grilled dishes.

It is not only the catering industry that is adapting. Many units are buying diesel generators to keep them running in the event of a power cut. Kyiv businessman Ilya Kenigstein has bought a large generator to keep his business, Creative States coworking centers, running smoothly. Last week he sold out all the places for solo work, and there is a waiting list of teams who want to rent the offices.

“After the war broke out, we understood how important it was to stay here,” says Zavertaylo. “We are here to work, create and support each other. All these complications only transform our values. We have to walk this path, and they [the Russians] won’t break us.”

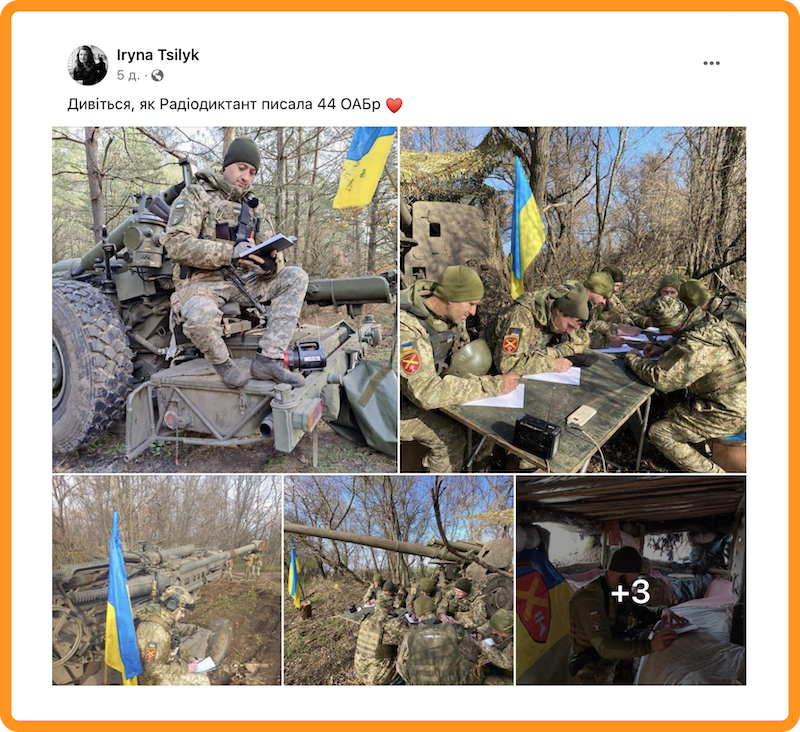

On 9 November, the Day of Ukrainian Writing and Language, the annual “Dictation of National Unity” organized by the Ukrainian public broadcaster went viral. The reason why? – its topic hit too close to home.

In this radio, TV and online gathering, audiences are invited to write down the words to an essay correctly. The piece, by writer Iryna Tsilyk, was dedicated to the concept of home, which the Russian invasion has stolen from millions of Ukrainians.

Having fled the war or taken up arms to defend their country, many listeners found themselves away from home, and united in writing words about a place dear to their hearts.

“Sometimes a home can fit into the size of a suitcase. We now are like those snails, [we] know the price of large migrations,” reads the essay.

Many were moved to tears, including the TV anchor of the event, Roman Kolyada, whose house was demolished by Russia’s war. Social networks were full of crying faces and damp sheets of paper.

Thank you for reading our 8th issue of European Focus,

Whether there will be a new wave of refugees from Ukraine depends on several factors. For example, the amount of modern anti-air missiles, endurance of the Ukrainian soldiers and the weather. Counting on the latter seems too risky, as humans can’t influence it just by pressing a button.

But the news from meteorologists is reassuring: this winter is expected to be unusually warm in Europe. That’s probably not good news overall ― but this year it is urgently needed.

See you next Wednesday!

Anton Semyzhenko