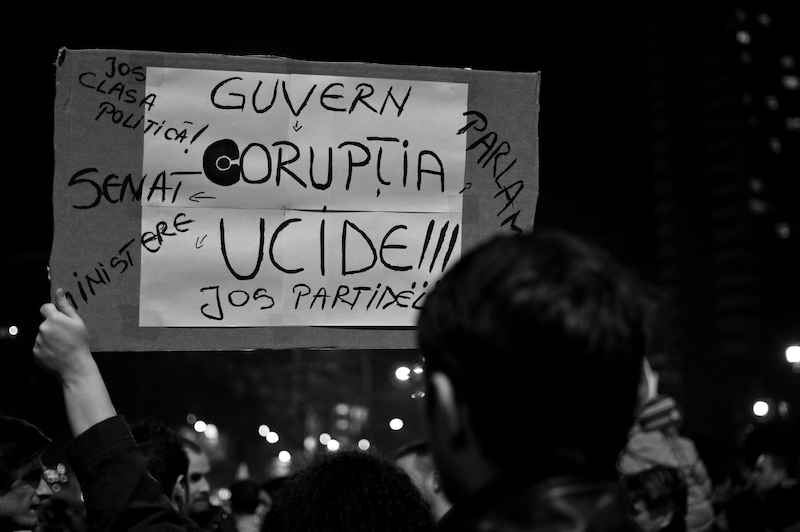

“Corruption kills” – hundreds of thousands took to the streets of Romania for weeks during the cold winter of 2015-2016, echoing this slogan. The #colectivrevolution was sparked by the tragedy at the Colectiv night-club in the capital Bucharest, where 64 people died in a fire in November 2015.

When the protestors realised the disaster was caused by irregularities overlooked by authorities, they turned against corruption with rage. As the expected results from years of a so-called war against corruption failed to materialise, the government of Victor Ponta resigned.

Since then, Romania is often cited as a positive example of anti-graft measures, which is both true and false. The judicial reform has transformed Romania step by step. Anti-corruption institutions have been set up. Over the last decade, corruption perception in the country has shown an upward trend. Following the protests, Romania’s corruption ranking has clearly improved.

Unfortunately, this is not necessarily because of the country’s outstanding performance, but because of increased levels of corruption in neighbouring countries. Tellingly, at the end of 2022, Austria vetoed Romania’s Schengen accession due to the level of corruption.

Most corruption cases still concern public procurement procedures in Romania, and there are still serious problems with Romania’s border controls, but vetoing Schengen is counterproductive.

Corruption cuts across borders. It is our common European problem. Whether we like it or not: we are bound together. Romanian society has a unique commitment to corruption-free politics and this needs European support.

The veto, on the other hand, is hurting the people, not the criminals. While several central European countries show a growing indifference to corruption, it would be wrong to punish a society that does not think that way and still resists.