Last summer, I had a discussion with Ukrainian journalists on the German Baltic Sea – the same coast where the North Stream 2 pipeline reaches the mainland in the village of Lubmin.

It wasn’t long before they, many of whom risked their lives on the Maidan eight years earlier in the revolution against a bent Moscow puppet regime, asked me: “There is so much corruption in Germany. Why does the public tolerate it?”

Germany – a corrupt country? The accusation would probably shock many Germans.

But this perception is not unusual. I can’t remember how often I’ve been confronted with this criticism in Hungary when conversing with investigative journalists.

The questionable involvement of the German car industry in Hungary’s corrupt economy and the perception that some German publishers have not covered themselves with glory when protecting their former media assets from takeover by Viktor Orbán’s clique are part of this tone. As is the view that Angela Merkel neglected Hungarian democracy in favour of German economic interests.

Sure, in Germany you don’t have to bribe the doctor to get an appointment. But while Germans cast a critical eye on corruption in other countries, they rarely turn their gaze on themselves with the same vigour.

How else can it be explained that Minister President Manuela Schwesig of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, who set up a cover-up foundation to realise North Stream 2 in tandem with Gazprom, is still in office today? Or that Putin’s friend and lobbyist, ex-chancellor Gerhard Schröder is not expelled from the SPD?

Hopefully we will soon realise that the strategic corruption “Made in Germany” can cause far more damage than everyday corruption in the “wild East” or “lazy South”.

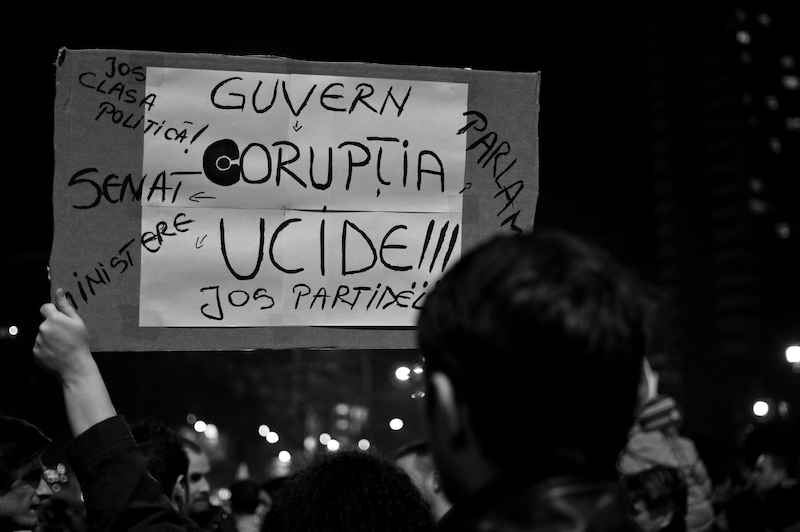

Then maybe I could tell Ukrainian colleagues about big anti-corruption protests in Germany – instead of demonstrations in Lubmin to stop sanctions against Russia.