Hi, and welcome to the first issue of European Focus,

Have you ever asked yourself why it’s also a problem for you personally that the European public sphere is still so weak?

“One doesn’t need to be a naive Europe enthusiast to ask this question,” our Polish colleague observed during our first weekly European Editorial meeting marking the start of this newsletter.

And he has a point, doesn’t he? Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine, the rise of right-wing populists in Europe, the fast spread of Covid-19 conspiracy theories, the climate emergency and the energy crisis are just a few examples that prove our European societies face great challenges and dangers that transcend borders.

It should be clear to everybody by now: We’re all in it together.

That’s why all of us, including European journalists and media, need to develop new habits: get out of our national bubbles and start discussing our common issues and problems with each other, instead of talking only about “the others”.

With European Focus, we’ll try to open a small European window each week in your inbox, with five short pieces written by our rotating team of authors and Editor-in-Chief.

Thanks for joining us in our experiment and please share the word!

Italy woke this week to the rise of the most far-right leader since Mussolini. In every European capital, the extreme right rejoiced. If public debate was more mature, we’d have foreseen not only Giorgia Meloni’s win, but also her tactics.

If we’d looked more closely at Budapest, for example, we would have seen that its strongholds of “illiberal democracy” serve as connection points for the European extreme right. I was there in April to report on elections; but what I found concerned Rome and Paris as well.

At the pro-Orbán Danube Institute, Erik Tegnér, lieutenant to French far-right presidential candidate Éric Zemmour, was a visiting fellow. There too was Hungarian President Katalin Novak, who previously teamed up with Lorenzo Fontana of Italy’s right-wing Lega to invoke the ‘traditional family’. Francesco Giubilei, a young ideologue of Meloni’s “conservative turn”, has also built ties with pro-Orban think-tanks.

Back in Rome, Meloni’s Fratelli d’Italia used the campaign to attack Peppa pig’s first same-sex couple. No coincidence. In Hungary, cartoons are reported to the media authority under anti-LGBT legislation. Orbán began his new mandate by declaring gender “the great problem of Europe”. Meanwhile, it’s business-as-usual between Hungary and Russia.

The more that Europeans understand how the extreme right handles identity politics elsewhere in Europe, the better they can debunk such tactics.

Days before Italy voted, Ursula von der Leyen said “we have tools” for countries that take illiberal turns. But the precondition for a strong European democracy is real democratic debate – and it starts from below. This doesn’t mean on social media alone: Mark Zuckerberg is already represented, with Meta’s 2022 budget to lobby Brussels at €6 million, up from €450,000 in 2015.

One crucial pressure group is still underrepresented: European public opinion. To build it up, let’s start with all of us.

In France, only 3.6% of television news was devoted to EU-specific topics between 2015 and 2020, according to a recent study by the French think-tank Jean Jaurès. By comparison, the EU average in 2018 was 13%.

The French figure drops further, to 2.5%, if we remove from the panel the public Franco-German channel “Arte”, which was founded in 1991 “to address cosmopolitan and curious citizens in Europe, especially in France and Germany”.

More than three decades later, European news and public discourse still seem to be ‘niche’ in French television programming.

It’s in The New York Times, it’s in The Wall Street Journal, it’s in Western European media. And it’s not going away. I’m talking about an outdated but persistent shorthand by which each of the Baltic countries is referred to as a “former Soviet republic” regardless of whether the article is about economics, digital leaps, tourism or Russia’s ongoing war of aggression.

Hence why this tweet by the Estonian politician Eerik-Niiles Kross – a sarcastic tutorial on how to describe other countries around the world – went viral earlier this month.

Here in Estonia we try to take it in good humour, but it actually demonstrates the shallowness of many large media and their editors. To be clear: the “former Soviet republics” never agreed to be part of the Soviet Union. They were violently forced into it. What we are or do now has little or nothing to do with our Soviet legacy.

An hour after Vladimir Putin ordered the mobilisation of 300,000 reservists, Viktor Orbán took to Facebook, not to express concern at a potentially more dangerous phase of the war in Ukraine, but to prod his finger at the West. “Energy prices are rising because of the misguided sanctions imposed by Brussels,” he wrote

Orbán’s siding with Russia and his undermining of a strong European response is not merely a domestic matter. The key question facing Europe is whether Russian imperialism can be stopped. False narratives are what help Putin win.

Orbán is looking for a scapegoat for his own mistakes: economic hardship, the weakening forint, rising debt, above-average inflation… That’s why he condemns European sanctions and remains silent on the Russian threat. His most important tool is the Hungarian language, with which he builds a private reality for his compatriots. Key to this is control of the press.

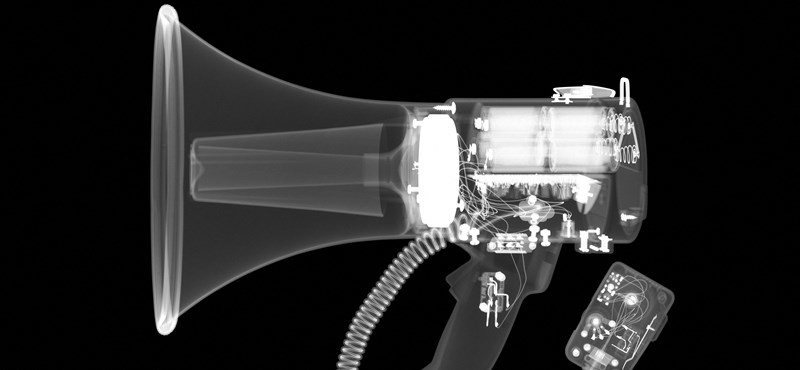

What Orbán says resounds a thousand times louder than anyone else’s words in Hungarian. And few people in his country are able to hear or read dissenting opinions in English, German, French, or even Ukrainian. Orbán has a monopoly on storytelling about the dangers posed by the outside world that – so the story goes – only he can save Hungarians from.

There is still a free part of the Hungarian press that sticks to its calling and tries to present all sides of what’s going on. But its power and possibilities are limited by the system. With unfair taxes, legislation and the power of oligarchs, the still-free media is squeezed into such a narrow space it cannot reach the furthest corners of the country.

The fate of Europe also depends on how much of the world Hungarians are able to see. And on what conclusions Europe’s citizens draw from Hungarian autocracy.

Johannes Hillje is a political consultant with a focus on pan-European communication and author of the book “Plattform Europa”, in which he elaborates his vision for a vital European public discourse.

You are critical of the way public spheres in Europe are still generally organised on a national basis. Why?

Although there is a lot of reporting on European issues in different national media, it is nearly always filtered by national interests. In most cases, the preferred perspective is: What is ‘our’ national benefit from a decision? But not: How does it serve our common European interest?

What are the risks?

Overall, this causes a democratic problem because we are living in a common political system. The nation states have handed over a considerable amount of decision-making power to the EU. Our common political institutions make decisions influencing the lives of all of us on a daily basis. But we don’t have a common and public democratic debate in which we could discuss these decisions together.

In addition, national governments will continue using this absence again and again for a blame game: Responsibility for unpopular decisions is often blamed on Brussels, while popular decisions are claimed to be taken by the national capital. There is hardly anyone correcting the stereotypical depiction of the EU or the other member states. So you can easily nourish anti-European sentiment.

What do you suggest?

In general, we need more shared communication spaces and truly European mass media. I also envision a real big shot: A common, publicly-owned digital European communication platform providing the infrastructure for a pan European discourse. It should provide not only news on European matters, but also entertainment and cultural content advancing a European identity. We should have political talk shows with European politicians and series, which tell stories of Europeans living together, for instance in border regions, during Erasmus or Interrail. And it could enable a truly pan European exchange including artificial intelligence-supported translations or virtual reality meetings.