Hi from Tallinn,

In my native Estonia, the Social Democrats called themselves “The Moderates” until 2004. This was because, after the collapse of the Soviet Union, anything associated with socialism was taboo. Forget about communism, that word automatically gets you a red card in this part of the continent. Ukraine, for example, has banned communist, socialist and left-wing parties outright.

My personal reason for hoping for a renewed European left is the hope that it will better address the concerns of disappointed citizens who might otherwise be inclined to vote for the far-right. In modern European politics, the far-right is often what the Ukrainian left used to be – sympathetic to the Kremlin.

Writing as a former judge of school debating tournaments, the far-right’s arguments on climate, the economy and rights of vulnerable groups are terrible. The kids I saw in competitions could dismantle them with ease. I find it unfortunate that so much of the European centre-right has flirted with the same ideas.

I hope you will find some recipes for a better political balance in this edition.

Herman Kelomees, this week’s Editor-in-Chief

In the general elections on 23 July the Spanish right party won the most seats in the Parliament, but without a majority to form a government. This leads to a deadlock or the re-launch of a left-wing-led government with the support of a myriad of regional parties. Jaime Coulbois, Spanish political analyst, explains why.

So the results in the Spanish elections surprised many, including the pollsters. What happened?

Before I start, a parenthesis: on Sunday, I was positive about an absolute majority for the [right-wing] People’s Party (PP) and [far-right] Vox. But it seems that the Socialist Workers’ Party (PSOE) government has been able to resist: the PSOE’s management has borne fruit, and the fear of political pacts with the far-right Vox helped the PSOE to get the “tactical vote”.

If the nationalists parties like Bildu (País Vasco independence supporters, far left) or the Catalan nationalists had made strong statements during the campaign, it would have made things more difficult for PM Pedro Sánchez. Without that, and with the nationalists seeming more rational than Vox, it’s more complicated for the right to get its narrative about the nationalists across.

When Pedro Sánchez won in 2019, he heralded a ‘red wave’ in Spain and in Europe. But after his defeat in the local elections in May, analysts talked of a ‘change of cycle’ to the right that didn’t materialise.

There is no contradiction in the fact that there is a social tendency towards the right, even the far right, but it’s still not enough to win a majority to form a government, especially in a polarised society like Spain. We are seeing attitudes that we would never have seen a few years ago: from Spanish nationalism to Francoist remembrance.

How was this avoided in Spain, when we see it all around Europe?

This discourse that previously was hidden has increased in public. But that’s not incompatible with the general public opinion. Spain is an exceptionally tolerant country regarding LGBT rights, and the immigration problem is very different from the rest of Europe: our migration does not have the strong cultural, linguistic and religious barriers that are in other European countries, and tensions with immigration may not have surfaced yet.

Nine political parties with the words ‘communist’, ‘socialist’ and ‘left’ in their names have been banned in Ukraine since its independence in 1991. Six of them were forced to suspend their activities after Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine began.

In a post-Soviet state, Ukraine’s leftists often have ties to Russia and even promote a pro-Moscow agenda. Now this position has backfired on them.

The ricochet has also hit Ukrainian society: now there are no political parties with well-established leftist policies. Centrist and right-wing parties don’t tend to pay enough attention to issues such as social equality or workers’ rights. Therefore, quality discussions on these topics are currently not on Ukraine’s political agenda.

Now that the 2024 EU elections are getting closer, one question haunts me: has a progressive alternative to the rampant right-wing really been tried? This further obsesses me due to the place from which I write, Meloniland.

Even before she became Italy’s prime minister, Giorgia Meloni negotiated a tactical alliance with the European People’s Party; this so-called moderate right has broken the cordon sanitaire and normalised the extreme wing. Europe could shift to the right in 2024. Faced with this scenario, one would expect an effective and united response from the left.

When the left joins forces, it works. In Spain, the Sanchez-Diaz duo counterbalanced the surge toward the right. At the European Parliament, the Socialists, the Greens, the Left and part of the Liberals managed to form a majority to defend the Green Deal against right-wing attacks. The French left-wing “Nupes” alliance had a good debut in last summer’s legislative elections. The struggle for social and climate justice is mobilising voters.

But political leaders are reluctant to act accordingly. At an EU level, the Socialist group’s president Iratxe García Pérez is still hoping for a grand coalition with the EPP, even though its leader, Manfred Weber, is the normaliser of Meloni and the extreme right in Europe.

Even at the epicentre of the far right, in Italy, the alternative appears weak and disorganised. Were it not for the internal divisions in her opposition, Meloni would not have won the government so easily.

But now that we are witnessing the Orbanisation of Italy, the country’s Democratic Party has been forced to change: the open race for the leadership was won by Elly Schlein, who promised to give the left a new boost. The proposal for a minimum wage, supported by all opposition forces, is a first positive signal in the Spanish style.

It remains to be seen to what extent the left will be able to generate new momentum.

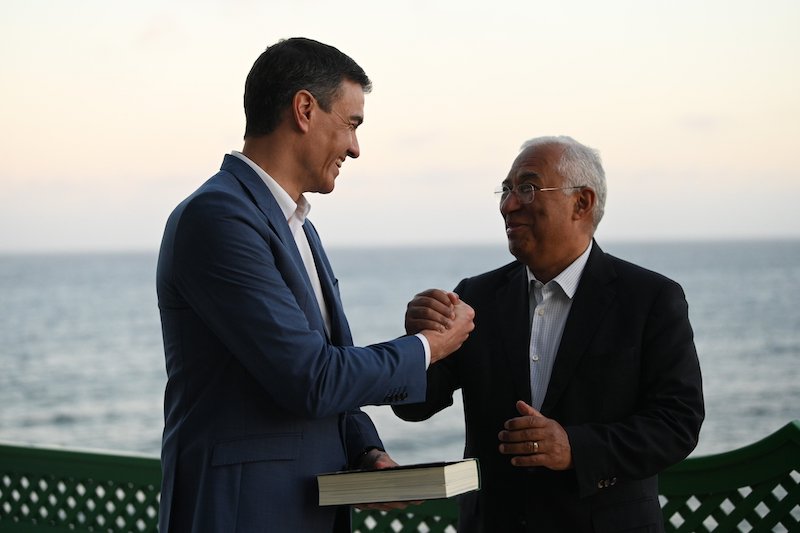

“Pedro Sánchez is not just a friend or a partner, he is someone with whom I have worked very closely in recent years, in the ‘Iberian exception’ for energy prices, or the battle we’ve fought together to create a programme for the structural transformation of our economies.”

– António Costa

In contrast to many countries in Europe, the far right will remain out of government in the Iberian Peninsula – at least for now.

In Portugal’s last election in 2022, António Costa’s Socialist Party won a majority to form the government, but over the past year it has been criticised from both the left and the right. Cases of corruption, inflation and a lack of vigour in tackling a housing crisis have left 52% of Portuguese saying the government has performed “bad or very badly”.

Could this mean that Portugal will move to the right in the next elections? If so, how far? 63% of Portuguese people don’t want an electoral pact between the centre right party PSD and the far-right Chega. Luís Montenegro, leader of the PSD, confirmed this weekend that such a pact is not his intention.

At the moment, the Iberian exception stands.

Will an eco-activist save Germany’s left? On 17 July, the leadership of “Die Linke” announced that Carola Rackete would be one of the party’s four top candidates for the 2024 European Parliament elections. This was nothing short of a coup.

Rackete rose to international fame in 2019, when she captained the Mediterranean rescue boat “Sea Watch 3” into the port of Lampedusa, carrying 53 migrants, although Italy’s authorities had forbidden her to dock. Furthermore, Rackete is a climate researcher and activist.

For years, “Die Linke” has been struggling, mainly because of internal conflicts. On the one hand, it includes young academic leftists from the cities, for whom climate change, LGBTIQ rights and the support of refugees are important. On the other hand, the party contains the older generation of leftists, who want to see more focus on workers’ rights.

Many of the latter are attracted to the rather controversial former leader of the party’s faction, Sahra Wagenknecht, who has polemicised against the younger generation for being “lifestyle-leftists” and strongly criticised Angela Merkel for her 2015 decision to allow refugees into Germany. Wagenknecht’s public statements often openly contradict her party’s policy. These conflicts have caused a loss of voters and members. In recent months, Wagenknecht has openly flirted with the idea of forming her own party.

For a long time it looked as if the party’s top brass wouldn’t be able to resolve these conflicts. However, on 10 June, the leadership asked Wagenknecht to resign from Bundestag. This marked a turning point.

The nomination of Carola Rackete is another milestone in this new direction. With a focus on topics such as climate protection and open borders, Rackete stands for exactly the opposite of Sahra Wagenknecht.

Thanks for reading the 40th edition of European Focus!

The result of the Spanish election proves that it is too early to say goodbye to the European political balance as we know it.

Whatever your personal political choices, I hope this edition helped you think about whether some better arguments are missing from the political debate that directly affects you.

Feel free to send your thoughts to info@europeanfocus.eu!

See you next Wednesday!

Herman Kelomees