Hi from Madrid,

Migration is back in the public eye. On Tuesday morning, I was checking the international press and saw the Polish media talking about the arrival of a ‘patera’ (boats that transport illegal migrants) to the Spanish coast. I wondered why such a small piece of news had made it to the Polish press. Then I realised: it is electoral season.

That’s also happening in Slovakia, where the anti-migration narratives have plagued the campaign. And as our Italian colleague told us, the narrative championed by right wing PM Giorgia Meloni has already been bought by the European Union. Even though in some migration routes, such as through the Balkans, we’re seeing some decline. But the numbers sometimes do not give the full picture of the nuances of reality.

Alicia Alamillos, this week’s Editor-in-Chief

One of the Italian prime minister Giorgia Meloni’s preferred catchphrases is about her “reshaping” Europe’s approach to migration. She has also appeared several times together with Ursula von der Leyen, the President of the EU Commission, and has demonstrated her actions on the issue.

At that time in mid-August, when most Italians were on holiday, data from the Ministry of the Interior revealed the bluff: in 2023, migrant landings have more than doubled compared to the previous year. From 1 January to 31 July 2023, more than 90,000 migrants arrived. During the same period in 2022, when Meloni was not governing, the figure was close to 41,000. The flows from Tunisia almost tripled compared to the year before.

Let’s look again at the image of Giorgia Meloni alongside Ursula von der Leyen and Tunisian autocrat Kais Saied. The Italian premier seemed triumphant: she acted as if, with the EU-Tunisia memorandum, the ‘migrant issue’ would melt away. The President of the European Commission even declared, during the State of the Union in mid-September, that she would sign similar agreements with other countries. Meloni and von der Leyen appeared more united than ever.

And they were, but again this was a bluff. To date, the only point on which Giorgia Meloni is really influencing the whole of the European Union is the definitive abandonment of the principle of solidarity. Until a few years ago, the debate between European governments was about the relocation of migrants in the EU. Italy was very interested in this issue – but now, with aggressive right-wingers sharing power in Italy, the premier has said that she has given up discussing it. She will only discuss strict borders.

While the citizens of Lampedusa are confronted with increasing landings, the first problematic border is in Meloni’s propaganda, between facts and the narrative.

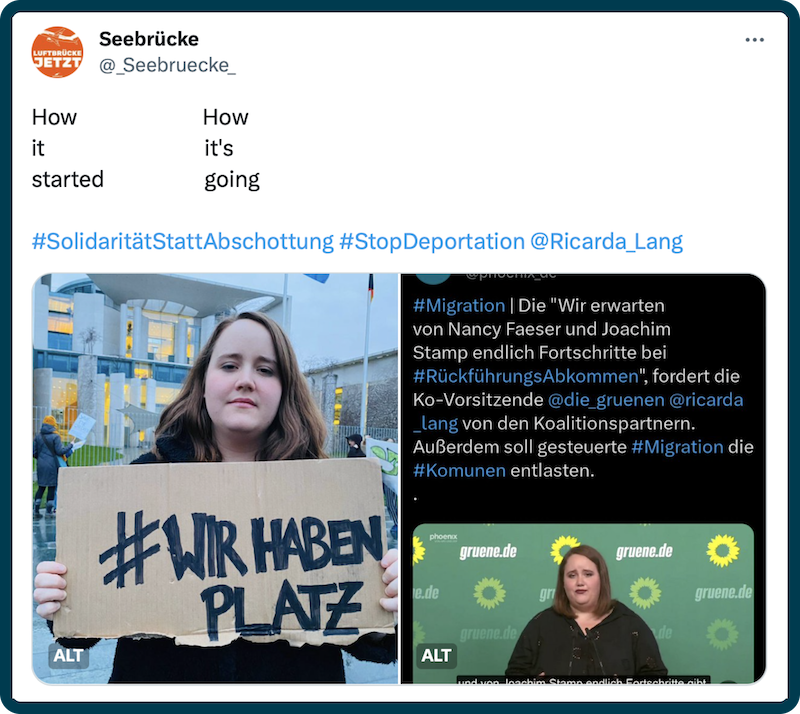

Not so long ago, the current German Green Party co-chair Ricarda Lang took to the streets to call for more refugees to be welcome in Germany. But a few days ago, on the subject of facilitating deportations for asylum seekers without a valid reason to remain in Germany, she made an interesting statement. Lang demanded publicly: “We expect the Minister of the Interior to finally make progress on the issue of repatriation agreements.” The conservative CDU, the liberal FDP and the social democratic SPD have all called for a stricter migration policy in recent months.

Maybe, this decision by the Greens came out of a fear they will lose the state elections in Bavaria and Hessia, which will take place at the beginning of October. But this is also part of a bigger political picture: The discourse in Germany is sliding to the right. Today, 16.2 percent of the German population have xenophobic attitudes, compared with 4.5 percent two years earlier, according to a new study.

Jozef Lenč is a political scientist who teaches at St. Cyril and Methodius University in Trnava and often analyses politics in Slovakia for the local media.

According to a new Ipsos survey, illegal immigration is one of the biggest concerns of Slovakians, ahead of the parliamentary elections. Some parties have focused on this issue, especially the former ruling party Smer, which is leading in the polls. Why is this?

The narrative on illegal migration can help any political party that can properly grasp this topic, including parties that have positive solutions to the migration crisis. Most often, however, political parties of the extreme or alternative right try to gain popularity through this kind of topic.

In the case of Smer [left-wing populists], they have understood that this could be a way to exploit the current mood in society, and it can cover-up investigations into corruption or the need to tackle the country’s economic problems.

Why has the issue of illegal migration resonated among politicians and in the media for several weeks?

The topic of illegal migration will stay here for a long time. But if something spectacular does not happen in this regard, the topic will disappear due to others presented by the extreme and alternative right-wing parties, like the protection against liberalism.

Political parties and the interim government partially blame Smer for today’s migration problem (from its time in office), but this has not harmed this party. Why?

The effect of the possible cancellation of the ‘confirmation’ [On the basis of a law passed by the Smer government, Slovakia issues a confirmation letter to illegal migrants, which allows them to stay in Slovakia for a certain period of time, but does not guarantee them the right to stay in the Schengen area] would only see results in a few months. Some voters may not have even noticed these confirmation letters, and it is enough for them that Smer leader Robert Fico is now pointing to illegal migrants.

Although the Balkan route for migrants has seen a decline of 29 per cent in the first half of this year, this remains the second most active pathway into the EU, according to Frontex, after the Mediterranean.

The numbers sometimes can deceive: this drop hides the individual stories of human suffering. North Macedonia’s Red Cross says thousands are in need of their help while traversing the Balkan route.

Migrants are often beaten or robbed by traffickers. Some looking to hitch a ride on top of or below a train suffer electrification and severe burns.

Last summer, my friends from NGOs and governmental organisations in Ukraine started speaking about a surprising problem in wartime. There were plenty of vacancies for jobs, with barely anyone to fill them. Different humanitarian foundations had established their offices in Ukraine, and Western partners had upscaled their operations, providing stable and well-paid jobs for locals ― but finding people for them was a struggle.

The problem was that most of these positions required good English, a university degree and thorough experience. Ukrainians who have these attributes are usually upper middle class, and are used to moving around from country to country. As the full-scale war broke out, many of them left Ukraine. This has been a strange impact of wartime migration.

Now this staffing crisis is felt throughout the economy. A coal mine in Pokrovsk, a city 40 kilometres from the frontline, pays its workers double ― and still cannot attract enough candidates. Some men have left the city, some have joined the army, and others are wounded due to hostilities. Who knew that Ukraine would feel a shortage of workers, as Russian missiles bombard our cities?

There are many other dimensions to Ukraine being on the supply side of the migration flow. Many of my friends are abroad and who knows if they will ever come back. To sustain itself in the future, Ukraine will need more people, maybe even millions. They have to come from somewhere.

It’s doubtful these will be Germans or Spaniards. The next wave of Ukraine-related migration will most possibly come from Central or South-East Asian countries. Economists and demographers are already starting to talk about this likelihood.

Thanks for reading the 45th edition of European Focus,

Next month we have elections in Poland, and next year, for the European Parliament. So we already know that the migration issue will be exploited by all sides. But a real solution is yet to appear.

In the meantime, we will stay critical and see what is behind the (mis)use of migration narratives.

See you next Wednesday!

Alicia Alamillos