Hi from Rome,

I was astonished, but not surprised when Matteo Salvini, a member of Giorgia Meloni’s government and the leader of right-wing populist Lega party, issued an injunction to limit Italy’s general strike last week.

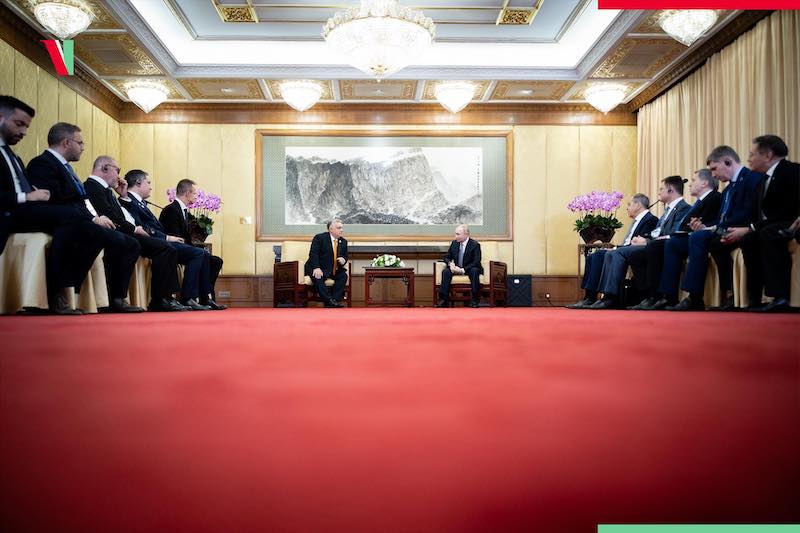

There’s nothing new in politicians trying to constrain workers’ rights in Europe. Previously, I saw Hungarian teachers being fired after striking under Viktor Orbán’s regime, and I knew that Rishi Sunak had just extended his anti-strike law. No matter if you are an authoritarian prime minister or a neoliberal leader: collective fights will give you the itch.

But are trade unions strong enough to resist these attacks? In some EU countries, unions are not widespread, such as in Estonia, or are toothless, such as in parts of the Balkans. When it comes to platform workers, it is hard to unite the workforce, as the European Trade Union Confederation tells us. And what about entire generations of precarious workers who feel unrepresented by old unions?

When our German colleague tells us about people feeling annoyed by strikes, I can understand why Salvini refers to “common sense” and Sunak pretends he’s “saving Christmas”. They touch on a weak point.

But collective bargaining means higher salaries and more rights. Uniting European labour forces can benefit our whole society. That’s why it’s crucial that we share a debate about the state of our trade unions.

Francesca De Benedetti, this week’s Editor-in-Chief

In Germany, many people see strikes as a nuisance, especially when it affects them personally. A train drivers’ strike last week is a good example of the reactions this industrial action provokes in Germany. Their union is small, but its members occupy central positions in rail operations.

A recent poll reveals that only 40 percent of those surveyed show an understanding of the actions of the train drivers, and 44 percent for recent strikes in the public sector. Some people complain that the strikers are taking the whole society as a “hostage”.

But there are other, much more sympathetic reactions to strikes in Germany.

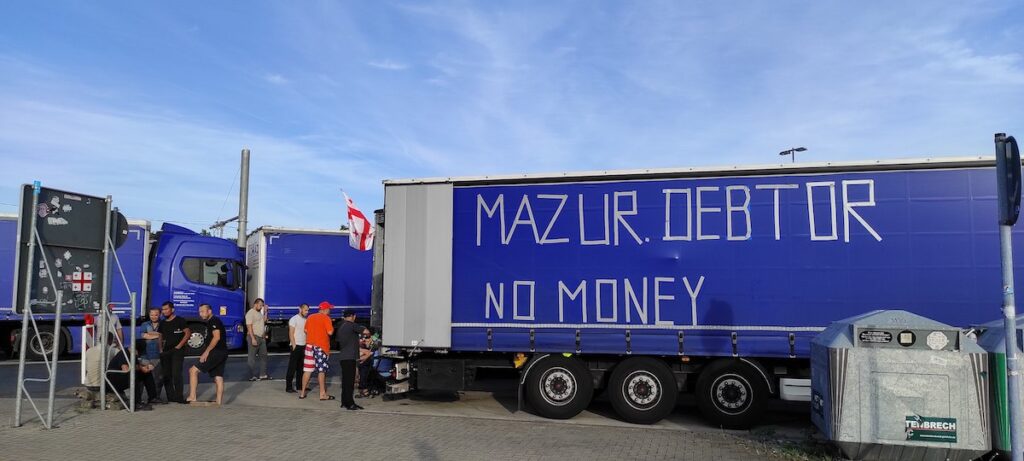

In April this year and for more than two months in late summer, there were strikes by truck drivers at a highway station in Gräfenhausen. At times 120 drivers, mostly from Georgia and Uzbekistan, who worked for the Polish company Mazur, but mainly drove in Germany and Austria, parked their trucks for weeks because they had not received their already meagre wages.

They succeeded: In the end they received the money to which they were entitled. Very few of these drivers were unionised. Nevertheless, there was a great deal of support for the strike from the trade unions: people brought food and, if needed, drove strikers to see a doctor.

This support probably meant that the strikers were able to endure their action for so long – and that in the end their strike was successful. This contrasts with other European countries, where the striking Mazur drives did not resist for such a long period. Even though the Gräfenhausen strike was not conventionally organised through a union structure, solidarity from unions somehow made the difference.

Just one of every 17 workers – six percent – is part of a trade union in Estonia. This is the lowest proportion among all the OECD countries. According to a labour expert, unions’ low popularity is driven by a “a particularly radical manifestation of neoliberal ideology”.

Kaja Valk, the newly appointed chairman of the Central Union of Estonian Trade Unions, admitted that it is “a very small number of people”, but she hasn’t presented how she plans to grow union membership.

A small number leads to a minor role for Unions in policy-making. The Unions do have a say in agreeing to the country’s minimum wage and the unemployment insurance tax. Outside of these responsibilities, they are hardly visible.

Ludovic Voet is confederal secretary of the European Trade Union Confederation (ETUC) and responsible for its work on the rights of platform workers, such as delivery drivers, cleaners, translators and web designers.

Why is it so difficult for unions to organise those employed in the platform economy?

The main reason is the imbalance of power and information asymmetry between platform workers and companies, who may have access to more data, resources and influence, and who can use various strategies to discourage unions from organising, such as surveillance, manipulation, intimidation or retaliation.

What are the problematic working conditions in the platform economy?

Companies often use the veneer of technological innovation to undermine workers’ rights by providing a service that is paid for by the task or by the hour, rather than by a salary or fixed contract. Workers have little or no control over the price of the service or their schedule. They are often classified as self-employed and have limited or no access to social protection or collective bargaining.

What improvements does the EU Directive on platform work bring?

The EU Directive should address these issues. However, some of the measures that would achieve this are actively being derailed by lobbyists.

At the core of the struggle is the employment status for platform workers. We have been clear from the start: no more bogus self-employment. We are also pushing for platform workers to have collective bargaining rights and trade union protection.

A right to transparency means that platform workers will be able to understand how the platform operates and how it affects their work and income. There should also be a ban on robo-firing, where workers are dismissed through automated decision-making systems.

What are examples of where platform workers have achieved improvements?

Workers have gone through years of legal process. But corporations attempt to stymie this progress by only applying the rulings to individual workers covered by the case, or not applying the rulings at all.

Against all odds, some workers have managed to organise, but these are rare exceptions. In Italy, for example, the Riders Union Bologna, negotiated a collective agreement with the food delivery platform Sgnam.

“In our textile factory there is no union. This allows our bosses to manipulate us. In a company near ours, the union representative is close to the owner, so it is no better there.

“I got fed up, so I started sending complaints to the labour inspectorate. One was for mobbing [harassment] – for not letting employees visit a toilet. Another was for unpaid overtime and one was because [the bosses forced me] to hand back part of my salary. But it was futile as I sent the complaints anonymously, because I feared being fired.

“Fear kills our hope.”

This 47-year-old single mother from Stip, North Macedonia, insisted on anonymity. During communist Yugoslavia, she said, women in her town were proud to be textile workers. The status meant emancipation and a decent wage. Through the active union, they also had a say in how the factory was run.

Now, the industry is a symbol of exploitation. The union has long turned into a puppet where owners and politicians, not workers, have control. This has stifled the voices of women, in particular.

The cost of living crisis, years of austerity under Tory governments since 2010, growing inflation, and a fall in real wages have provided a new space for trade unions in Britain, exemplified by a wave of strikes in 2022.

In addition to the ongoing strikes in different sectors, there has also been a growth in union membership, also driven by a large increase of women joining up between 2017 and 2020.

Historically, trade unions in the UK have secured workplace rights, including the minimum wage, maternity and paternity rights, pensions, holidays, and sick leave, and helped draw up the social agenda of the Labour Party, which was founded by unions and socialist societies in 1900.

While unions were central to these developments, they reached their peak in 1979, with 13.2 million members. Consequently, Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative government, as part of the Trans-Atlantic neoliberal consensus, antagonised unions front and centre in the 1980s.

Thatcher’s mantra was “There is no such thing as society”, which was key to how her governments (and those of her successor John Major) implemented legislation to reduce unions’ power and influence, through restrictions to the right of picketing, ballots for strike actions and preventing members from supporting other unions.

This setting also contributed to a progressive decline in union membership, which fell from its 1979 peak to below six million in the early 2010s.

While the miners’ strike of 1984-85 challenged Thatcher’s policies against unions’ actions, its outcome saw a victory of a neoliberal consensus that outlasted the conservative governments.

The return of the unions to the British stage after decades in the wings are a sign of hope and defiance for workers’ organisations in Europe. However, this contrasts with the British political scenery. The country faces a choice at the general election next year, between Tory PM Rishi Sunak’s anti-union legal position and Labour Party leader Keir Starmer’s centrist neo-Blairite stance.

Thanks for reading the 53rd edition of European Focus,

and thanks London for sending us positive vibes!

Yes, we can (strike). Yes, we can (unite). How great would it be to fight for our rights as Europeans…

Crossborder solidarity can make the difference, as our German colleague told us. Unity could be an elixir of youth for trade unions too.

Your comments and your stories are welcome at info@europeanfocus.eu.

See you next Wednesday!

Francesca De Benedetti, this week’s Editor-in-Chief