Hi from Skopje,

When I was young, my mind was imprinted with the image of a friendly neighbourhood cop. One of us. The “good guy”, here to help me if I got lost, and to protect me from the bullies.

I wonder, did 17 year-old Nahel, who was shot by the police in Paris last month, ever have the chance to be equally naïve as a child? Or did the police officers in his neighbourhood always spell trouble?

As I write these lines, France is shaken by the riots sparked by Nahel’s killing, and a line of graffiti in Ukraine asks a simple question that haunts me – “Who do you call when the police murder?”

I am not sure. But I do know it’s not only about France and police brutality, and is so often just a symptom of the deeply rooted illnesses of hatred, xenophobia and discrimination.

Siniša-Jakov Marusic, this week’s Editor-in-Chief

When it comes to public safety, France is an “anomaly”. This is the observation of several specialists, who have been concerned about the increase in fatal shootings by French police in recent years. The issue came back to the centre of public debate after the death of Nahel, a 17-year-old teenager shot by police on 27 June in the Paris suburbs, after refusing requests to stop his car.

This case is not isolated. French police have killed at least fifteen people since the start of 2022, due to the victims’ failure to comply with an order to stop – far more than their European neighbours. According to French police researcher Sébastian Roché, Germany has only recorded one fatal shooting at a moving vehicle in ten years.

His calculations show that between 2011 and 2020, the police and gendarmerie in France killed almost 50% more than the German police, and over three-and-a-half times more than the British. The victim is typically a man under the age of 27, with an African or North African-sounding name, living in a working-class neighbourhood close to major cities.

There are several possible reasons for this “French anomaly”. Researchers and MPs have pointed the finger at the reform of a law in 2017, which relaxed the use of firearms by police officers and led to a five-fold increase in killings of people in moving vehicles compared to 2012-2016, according to a recent study. The report also deplores shortcomings in the quality of candidates who serve in uniform officer training: almost one in five applicants is now admitted to the police ranks, compared to one in fifty ten years ago.

The increase in fatal police shootings has serious social consequences. They risk deepening the rift that divides French society into two rival camps: those who place order above all else, and those who denounce the racism and discrimination behind the deaths caused by the police.

In understanding police violence and its psychology, the United States has more expertise than its European counterparts. Paul Hirschfield is a Professor of Sociology at Rutgers University, who has studied police accountability.

Is there a psychological aspect of being part of a police force that explains police violence?

Police violence can often be explained by group psychology. Violence is also a procedural reaction: it is coerced, encouraged or enabled in different situations.

Many aspects of police activity evoke an “us and them” mentality. First, the police are an isolated, paramilitary organisation. Its performance is often judged by adherence to procedures and incentives of which the public has little knowledge. The police often feel that the public, especially their critics, do not understand their work.

The everyday reality of unrealistic or ambiguous policies that inevitably lead to police misconduct, combined with external scrutiny, fosters a culture of teamwork and solidarity but also makes officers more prone to cover up for each other’s mistakes.

Is it possible to avoid this mentality?

When it comes to policing disadvantaged or oppressed communities, eroding the boundaries between the police and the public can help. The isolated paramilitary structure may be useful for some purposes (like reducing corruption and increasing internal accountability) but it does little to foster empathy across cultural barriers and promote trust from the public.

What would you suggest to tackle the phenomenon?

This would require time and significant changes in centralised police forces. The preferred approach is the Scandinavian. The long training (three years in Finland, for example, as opposed to the short training in the US) at highly selective national police academies provides an opportunity to fully instill a spirit of national service and equality in police officers (not to mention ample training in tactical alternatives to violence). I don’t think it is a coincidence that in France, where issues of police and inter-community hostility are so prominent, police officers receive relatively short training, averaging nine months.

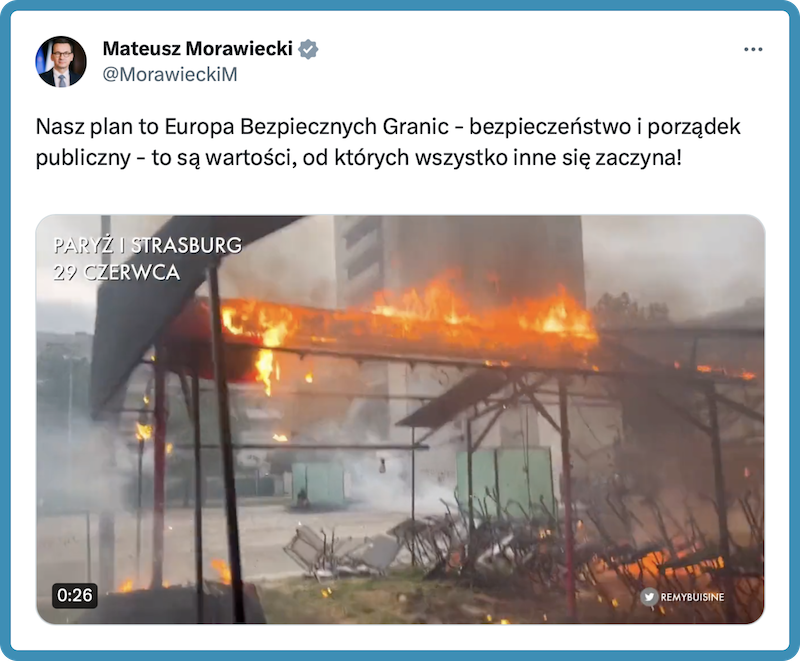

Nanterre and Marseille, France on 28 June – burning cars and the looting of shops. Kraków, Poland on 28 June – women walking through the sunshine in peace. These were scenes from a Twitter video that Polish prime minister Mateusz Morawiecki shared during the French unrest.

He was not the only populist leader capitalising on the events. In a Facebook post, Hungarian foreign minister Péter Szijjártó, who is a hardliner against migration like his Polish counterpart, wrote: “The French riots prove that it is impossible to integrate violent masses of illegal immigrants from other cultures.”

As well as scoring points at home, the Polish and Hungarian statements have a special message for the European Union. As the EU continues to debate its new migration pact, including voluntary relocation and solidarity, both central European countries made it clear they are ready to fight against the proposal which they consider is “forced upon them”.

They have both used their power of veto as blackmail before, so these might be more than empty words.

This is the number of times Kyiv’s public workers have painted over a specific line of graffiti, while leaving its neighbouring words and pictures intact.

The graffiti asked in Ukrainian “Who do you call when the police murder?”. This first appeared on 16 September, 2019, against the backdrop of numerous reports of unsanctioned police violence. The graffiti has constantly been restored by activists, and spread to other large Ukrainian cities.

As the full-scale Russian invasion started, the reputation of the police improved drastically: many officers are on the frontline, defending their country and sacrificing their lives. But the problem of police impunity still needs to be addressed.

As I read about France, I am getting flashbacks from my own country.

In June 2011, Macedonian Prime Minister Nikola Gruevski was revelling in yet another election victory when his political demise started, unmasking his authoritarian regime.

At his party’s celebration in Skopje, a policeman brutally killed 22 year-old Martin Neskovski who, ironically, was there to honour Gruevski’s win.

Initially the police kept the details quiet, but word spread on social networks. Hundreds of young people started protesting against the attempted cover-up, demanding “Justice for Martin”. By the end of summer, thousands were on the streets every day.

Authorities had to acknowledge the murder, and apprehended the police officer suspected of the crime. But he insisted he was off duty that day. No one else was held responsible.

And yet, I recall nothing was the same any more. Before, only the weak opposition cried foul. Afterwards, Gruevski’s tight grip on power started to loosen.

In power since 2006, Gruevski was finally ousted in 2017. One raindrop opened the floodgates. In 2014, due to a proposed change in the educational law, tens of thousands protested in Skopje demanding Gruevski stop interfering in elementary schools and universities.

In 2015, another wave of protests started, after the opposition published a series of leaked wiretaps from the secret police that showed the corrupt face of Gruevski’s regiment. Among them, one suggested that the authorities plotted to cover up responsibility for the Neskovski murder.

The “Colourful Revolution” continued until a new majority toppled the regime in 2017.

I was there. I followed these protests. I felt the energy and witnessed how much the demand for justice for Martin was part of it.

Then politics took over, and now we still receive warnings that police brutality is a problem. I wonder – will history repeat itself?

Thanks for reading the 38th edition of European Focus!

Have you ever played cops and robbers? In my case, nobody wanted to be a robber.

We would pick the weakest kid to be the robber, needlessly press him against the ground and savagely twist his arms to cuff him with our plastic cuffs as we revelled in our newly found power.

Don’t our adult societies do the same? Don’t we target an underprivileged group that we blame for everything and persecute them unfairly?

What a sick game.

See you next Wednesday,

Siniša-Jakov Marusic