Hi from Skopje,

Trains are everywhere in Europe. Whether travelling at high speed or a more leisurely pace, whether fancy or straight out of a Soviet dystopia, our continent and its progress could not be imagined without them.

Then why have they fallen out of fashion in recent decades? Are cheap flights and the convenience of cars killing the railway, and making it a relic of the past?

At the editorial meeting for this edition, one thing was clear – the topic is overwhelmingly complicated and among all the bottlenecks, different track gauges, border crossings and gaps in the current infrastructure that need bridging, one can develop a headache.

A bold ongoing European initiative aiming to revitalise this irreplaceable infrastructure, it seems, is not enough, and rails in our countries are still moving at different speeds. In some places, trains have literally reached the end of the line.

What is needed, it seems, is a common European mindset, and then a lot of joint work to bring rail back on track.

Europe’s most touristic destination has for years been unreachable by international train. Meanwhile, Greece’s domestic lines paint a similarly grim picture. Chronic financial and staff shortages, corruption and disregard for EU rules are the main causes for the current decline.

In 2011, trains linking Thessaloniki with the Balkans and then to the rest of Europe were suspended by the Greek government. They relaunched briefly in 2014, before being cancelled again for good.

Jointly operated by Turkey and Greece, the train connecting Thessaloniki to Istanbul launched in 2005, but was slashed in 2011 due to cost-cutting by the then Greek state-owned company TrainOSE.

Turns out, these lines simply could not keep pace with cars, buses, and planes.

The Thessaloniki-Alexandroupolis route, the most important domestic railway line since 2010, has suffered from a lack of staff and maintenance, placing the infrastructure in an atrocious state. The 440 km route now takes 8.5 to nine hours. George Nathenas, a traffic expert, says that was also causing problems for the cancelled Thessaloniki-Istanbul route.

Over the last 30 years, despite available funding, the modernisation of the network has been one big failure.

“The memorandums imposed [by the IMF, EU and Greek Government] due to the Greek financial crisis caused the laying off of experienced personnel and the separation of the national railway company into independent legal entities that dispute among themselves, and this also had implications,” explains Nathenas.

This degenerated from bad to worse. Last February, 57 people lost their lives in a head-on collision between two trains near Tempi Valley, provoking a national outcry. A prosecutor’s investigation discovered the automated system for re-routing trains, which would have prevented the human error, did not work.

In September, severe damage on the railway network was caused by the storm Daniel. The government promised a full recovery of the damaged railway – but only in the next 1.5 years. Even if this is achieved, this would still be a drop in the ocean of problems that need to be solved.

If there was a book of negative world records, the Romanian State Railway Company (CFR) would certainly be breaking some of them. In a country cut in two by the Carpathian mountains, travel is difficult between the main regions, therefore rail transport is of strategic importance. However, the state-owned passenger transport system is falling apart.

70 percent of the railway lines are in need of rehabilitation. The average speed of trains is less than 70 km/h – the same as 150 years ago. Three out of four trains are delayed. In 2022 alone, the total amount of delays accumulated was equivalent to eight years.

Jon Worth has probably travelled every train route in Europe. Founder of the ‘Trains for Europe’ platform and a regular commentator on the subject, he has a broad perspective on the opportunities and problems of European rail connectivity.

Europe has, in general, fairly well-developed rail networks. Is this a good starting point for a truly connected continent?

We don’t really have a European rail network. We have 27 national railway networks with some international connections between them. There are lines that cross borders, all of them of lesser quality, and less used. And this happens more or less at every single border crossing between European countries. There are even cases where one train stops before the border, and the other train starts after the border, but a few kilometres away, with nothing in between. That’s the key problem: to have a European mindset to think about trains.

But there are technical problems: track gauges are not always the same in bordering countries, there are different electrical systems, and national railways are centred on capital cities.

Partly. But the technical problems are less important than the mentality and coordination problems. For example, in Spain, which has a different gauge from France, you have to make sure that the timetables are coordinated so that passengers can get to the station and take the next French train. There are simple solutions for these technical problems if the companies are willing.

With all the talk of going green, and the backlash against short-haul flights, is there a window of opportunity to revitalise rail transport?

There is a great opportunity. Especially for leisure travel or weekend excursions. Hungary is a very good example, there has been a massive increase in trains going from Budapest to the countryside, instead of people taking cars. 2020 was a record year for rail ticket sales, I think 2023 will be an even bigger record year.

The problem is that the demand is there, but the question is whether the railway companies will be able to meet this demand. I am not entirely sure. In France, for example, their high-speed trains have fewer seats than a decade ago.

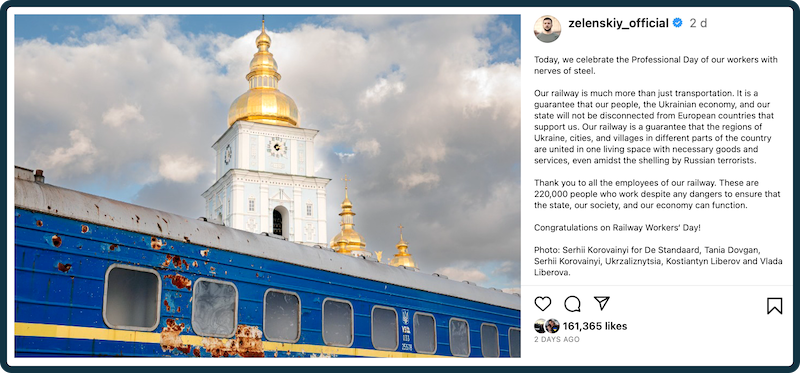

An image of this railroad carriage, which is exhibited in one of Kyiv’s central squares, has gone viral in Ukraine. It was part of a special train that regularly evacuated Ukrainians from the almost-encircled city of Irpin in the first days of the full-scale Russian invasion in 2022.

On 3 March, the carriage was hit by shelling and badly damaged by shrapnel. Fortunately, there were no casualties and the train continued its journey.

Before the war, the state railway company Ukrzaliznytsia was seen as a problem: inefficient, corrupt, opaque, and too big to be closed down due to its up to 400,000 employees. Several attempts to reform the company had failed.

In the crisis of the last two years, however, its shortcomings proved to be a lifesaver. As a centralised state structure, it is reliable and fast in evacuations. Its unprofitable and widespread network, with many branch lines, meant that for many communities in at-risk areas, the railways were sometimes the only way out of danger.

And, despite the everyday challenges of life in Ukraine, there are no delays.

As I was dragging my suitcases across the Hungarian-Serbian border in the summer heat, I had my doubts about taking the train. The year was 2004, the destination was Montenegro, and I was ready for a 20-hour night journey from Subotica, Serbia to Bar on the Adriatic coast. However, due to a huge queue of cars, we had to cross the border on foot to reach our departure point.

With these beginnings, the holiday was – naturally – the best time of our lives.

Since that August day, I have become a firm believer in rail travel, criss-crossing the continent from Narvik to Naples. It was a far cry from the 90s, when Hungarian students travelled around Europe on fake interrail tickets, but it was cheap, efficient – and a real coming-of-age-adventure.

The years went by, my love of travel remained, but with the advent of budget airlines, I became a frequent flyer. Although it is fast and inexpensive, I miss the train journeys where I could comfortably stretch my legs and watch the forests pass by.

The problem is: I could not travel by train even if I wanted to. Our night train from Budapest to Venice has been cancelled, there are no more trains from Budapest to Montenegro, and to travel to Brussels – a trip I make every month – I would have to drive to Vienna, where the train departs.

Passenger rail transport has sadly become unprofitable in Europe. While governments support national lines, international ones are so expensive that people choose to fly, even for smaller distances.

After more than a decade, I finally managed to take a night train again this May. Memories instantly came rushing back, as I lay in the compartment taking me from Chełm in Poland to Kyiv, where the train is a lifeline for the war-torn population. Ironically enough, sometimes it takes a war to make us appreciate what we have.

Thanks for reading the 51st edition of European Focus!

Instead of a headache, I hope we’ve offered you a productive brain tease.

Think of the last time you took the train? Was it a local line or cross border? How was it? What was missing, and how can things be improved in your region?

As always, we are interested in your feedback. You can write us an email to: info@europeanfocus.eu.

See you next Wednesday!

Siniša-Jakov Marusic