Hi from Paris,

Last Thursday, immediately after our regular meeting for European Focus, I took to the streets of Paris to protest against the pension reform. With colleagues from Libération, we marched alongside hundreds of thousands of strikers.

As is often the case, the demonstration ended badly. I went home with painful lungs and eyes reddened by tear gas.

Seen from elsewhere, these demonstrations, which have lasted for more than two months, may seem difficult to understand. We are often told that the French have one of the lowest retirement ages in Europe.

Compared to other countries, we are privileged. I don’t have to consider working until 78, like my Estonian colleague, or buying a flat to secure an income for my old age, as some Poles must do.

Our parents and grandparents battled for the public funding of pensions and reduced working hours we enjoy today. If we want to keep these rights, it is our turn to fight.

Nelly Didelot, this week’s Editor-in-Chief

“I don’t know if the government realises that we die before others do,” said Daouda, a 49- year-old waste collector. Since 6 March, he and his Parisian colleagues have been on strike against France’s pension reform to raise the retirement age by two years.

Today, waste collectors who are employed in the public sector are allowed to retire at 57, because of the physical exertion demanded by their occupation. The new law will increase this to 59. For those employed by private companies, the age will jump from 62 to 64.

“People have no idea of what this profession involves,” says Pascal, 64, a retired waste collector, who joined the picket line in Ivry-sur-Seine, in Paris’s suburbs, to support his former coworkers.

Isabelle Salmon, a medical practitioner who has written a PhD about working conditions of this profession, argues this job “is probably one of the most trying, because it combines physical constraints with uncomfortable postures and exposure to the weather.”

Going on a continuous strike is a hard decision to make. David, 49, a waste collector, says he will face problems paying his rent. Due to his strike action, his employer will withdraw at least 14 days from his 1,400 euro monthly wage. He hopes that it will be worth it, and that the government will finally give in to the workers’ demands.

Like his colleagues, David must work in all conditions. These key workers have not forgotten the morning after the Paris terrorist attacks in November 2015 or the first Covid lockdown in March 2020.

“At that time, with Covid, the government promised to change its policy for front-line jobs,” remembers Christophe Farinet, a waste collector and vice general secretary of the General Confederation of Labour (CGT). “Not only for us, but also for the cashiers, security guards and cleaning staff, who can’t afford to go on strike today. Three years later, this is where we are.”

l will be 68 years and three months old when I can retire in December 2056. This is what the pension calculator on the webpage of Estonia’s social services authority said to me.

The app only needs to know my year of birth, 1988, to make the calculation. 68 could be considered my default age of retirement within the Estonian system, which takes into account life expectancy. If life expectancy rises, my retirement age will follow suit.

I could choose to retire up to five years earlier at 63. In this instance, I will beleft with a measly pension worth one quarter of my current salary. In fact, even if I retired at 68 years, my state pension (assuming that it would increase with inflation) would not even be enough for my rent and utility payments.

Margus Tsahkna, a former minister of social affairs who is helping negotiations to form Estonia’s next governing coalition, admitted the state will not be able to pay pensions the same way in the future. “This is a brutal message,” he said, adding there is no alternative to reform.

I played with the calculator to see how much I needed to delay my retirement to survive on a state pension alone. It was not possible to calculate a pension beyond the age of 78. If I retire at 78, I would receive two-thirds of my current salary, which would leave me without any financial room for manoeuvre.

The age of 78 is 23 more years than the number of “healthy years” an average Estonian man lives, according to state statistics. This means that Tsahkna’s assessment of the pension crisis is right, but there is not yet a solution, other than to exclaim: “Everyone for themselves!”

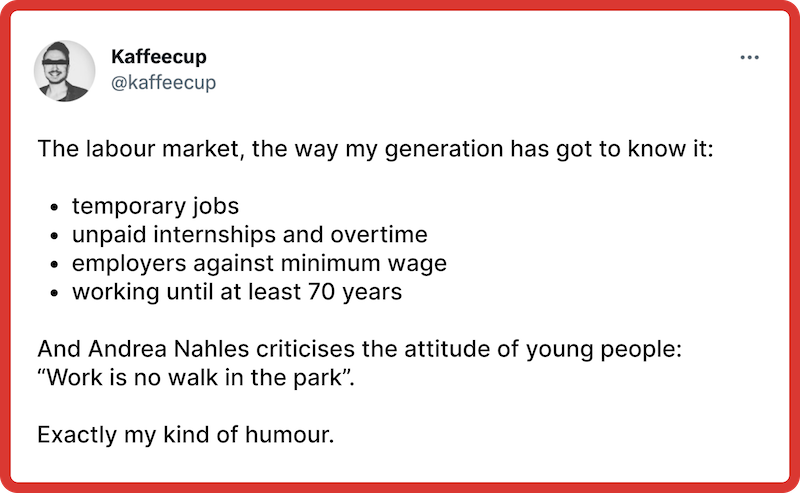

“Work is no pony farm,” Andrea Nahles, head of the Federal Employment Agency warned the younger generation recently in a statement that went viral on social media. The comment can be translated in English as “Work is no walk in the park” and the former Social Democratic Minister of Labour indicated that the young should prepare to work more.

But they don’t want to. What they want is a better work-life balance. In a survey last year, 57 percent of young people between 16 and 29 said that their private life was more important to them than their professional career.

With the retirement of the “boomer” generation, Germany will face a lack of seven million people from the workforce by 2035. This also poses a challenge to the financing of the pensions. The state is likely to fund large parts of the difference – and someone needs to pay taxes for this.

It is an unpopular truth: in Poland, few people can count on a decent pension in the future.

A decade ago, Minister of Economy Waldemar Pawlak said bluntly: “I don’t believe too much in state pensions. I try to secure my future through savings and a good relationship with my children. This will be more secure than these various state chimerical solutions.”

The belief that the state will pay a decent pension after 1989 has never been particularly strong in Poland.

Many Poles have taken matters into their own hands, just as the capitalist system had taught them to do. Knowing they won’t have a decent pension, they invested in the property market.

After the fall of communism, pouring capital in real estate has become the national sport of Poles. Prices have risen at a tremendous rate, especially in Poland’s largest cities. Cheap loans have made it possible to buy a flat without a lot of capital. Many treated it as an investment. Some individual buyers had more than a dozen flats on credit. But this process has made another problem worse: access to housing.

More and more flats were built, but as many as two million of them are standing empty. A large proportion of these are flats that people have bought as an investment, with a view to selling them off at a profit.

As a result, rental prices have also risen. Today,only a small minority can afford a mortgage. Therefore, the majority of Poles will be condemned to whatever pension the state will offer them in the future.

An even bleaker future awaits those who are currently entering the labour market. By 2060, they will barely receive the equivalent of 25% of their final salary as pensioners.

“Grandparents helping their children become independent or paying for their grandkids’ school is proof the system doesn’t work. This year, my pension will grow by 8.5%, but you will probably not get a pay rise, and if you do, it will be 3% at most. It is unfair that we still get better and better pensions: just for starters, I have bought my house, while my son loses 40% of his salary on rent.”

Mariano Guindal, 72, is a pensioner from Barcelona who feels privileged. He receives the maximum pension (which is more than 3,000 euros per month), and it keeps increasing. But he feels this is unfair: in his opinion, the pensioners are a ‘protected’ social group, spoilt by successive Governments for electoral purposes. In Spain, there are ten million seniors, which means ten million voters out of a total of 36 million.

Thanks for reading the 25th edition of European Focus,

I hope you liked this week’s edition.

If you want to learn more about us and about pensions in our different countries, please join European Focus’s Twitter Space on Thursday at 6:30 PM CET.

My colleagues from Italy, Spain, Ukraine, Germany and Hungary will debate one simple but fundamental question: For how long should we work?

See you next Wednesday!

Nelly Didelot