Hi from Budapest,

“Corruption is what you are missing out on.”

When you ask a Hungarian how they define corruption, this sentence from the country’s most famous stand-up comedian, Géza Hofi will probably pop up in the conversation.

In the twenty years since Hofi died, the definition has not changed, but its perception has. Corruption is often viewed as something that only happens in the offices of politicians or businessmen, and sometimes even in the European Parliament.

But is it so distant from our everyday life?

Last week, when a colleague of mine boarded a bus in the countryside, he was amazed when the driver offered to take him for 200 HUF cash-in-hand, if he chose not to buy an ‘official’ 400 HUF ticket. He declined, but some other passengers may have not.

The truth is many forms of corruption have become so entrenched in our societies, that we do not even notice when they happen right before our eyes. This week’s newsletter tries to explore how different European countries are fighting to change that perception.

Last summer, I had a discussion with Ukrainian journalists on the German Baltic Sea – the same coast where the North Stream 2 pipeline reaches the mainland in the village of Lubmin.

It wasn’t long before they, many of whom risked their lives on the Maidan eight years earlier in the revolution against a bent Moscow puppet regime, asked me: “There is so much corruption in Germany. Why does the public tolerate it?”

Germany – a corrupt country? The accusation would probably shock many Germans.

But this perception is not unusual. I can’t remember how often I’ve been confronted with this criticism in Hungary when conversing with investigative journalists.

The questionable involvement of the German car industry in Hungary’s corrupt economy and the perception that some German publishers have not covered themselves with glory when protecting their former media assets from takeover by Viktor Orbán’s clique are part of this tone. As is the view that Angela Merkel neglected Hungarian democracy in favour of German economic interests.

Sure, in Germany you don’t have to bribe the doctor to get an appointment. But while Germans cast a critical eye on corruption in other countries, they rarely turn their gaze on themselves with the same vigour.

How else can it be explained that Minister President Manuela Schwesig of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, who set up a cover-up foundation to realise North Stream 2 in tandem with Gazprom, is still in office today? Or that Putin’s friend and lobbyist, ex-chancellor Gerhard Schröder is not expelled from the SPD?

Hopefully we will soon realise that the strategic corruption “Made in Germany” can cause far more damage than everyday corruption in the “wild East” or “lazy South”.

Then maybe I could tell Ukrainian colleagues about big anti-corruption protests in Germany – instead of demonstrations in Lubmin to stop sanctions against Russia.

Ranked 14th best by Transparency International in terms of perceived level of public sector corruption, Estonia is less dodgy than the UK, France or Japan. This may seem bewildering to Estonians themselves.

Take Kohtla-Järve, the fifth-largest city. At the end of last year, nine of the 25 members of the city council and the governing coalition were declared suspects in a bribery and influence peddling case.

This was followed by the council’s attempt to put together a “rainbow coalition of the uncorrupt”. In the end, only nine of the “uncorrupt” 16 council members voted in favour of it, leaving the city with a minority government. How do Kohtla-Järve’s citizens perceive corruption? Probably as something right before their eyes.

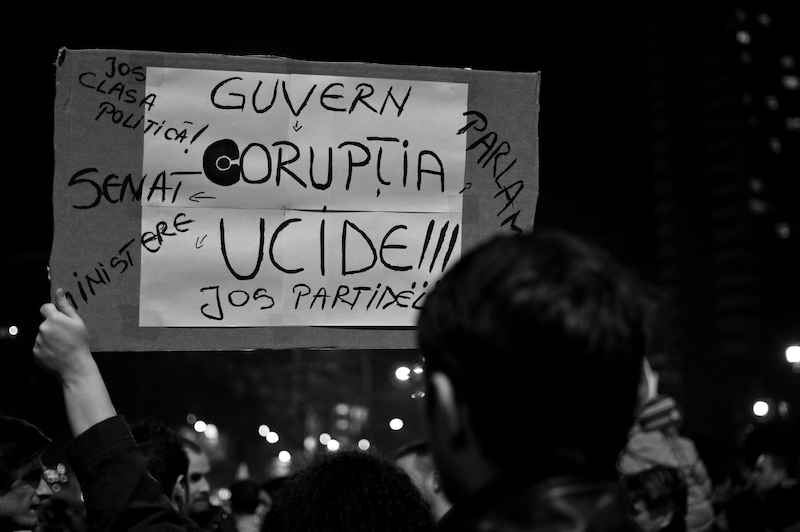

“Corruption kills” – hundreds of thousands took to the streets of Romania for weeks during the cold winter of 2015-2016, echoing this slogan. The #colectivrevolution was sparked by the tragedy at the Colectiv night-club in the capital Bucharest, where 64 people died in a fire in November 2015.

When the protestors realised the disaster was caused by irregularities overlooked by authorities, they turned against corruption with rage. As the expected results from years of a so-called war against corruption failed to materialise, the government of Victor Ponta resigned.

Since then, Romania is often cited as a positive example of anti-graft measures, which is both true and false. The judicial reform has transformed Romania step by step. Anti-corruption institutions have been set up. Over the last decade, corruption perception in the country has shown an upward trend. Following the protests, Romania’s corruption ranking has clearly improved.

Unfortunately, this is not necessarily because of the country’s outstanding performance, but because of increased levels of corruption in neighbouring countries. Tellingly, at the end of 2022, Austria vetoed Romania’s Schengen accession due to the level of corruption.

Most corruption cases still concern public procurement procedures in Romania, and there are still serious problems with Romania’s border controls, but vetoing Schengen is counterproductive.

Corruption cuts across borders. It is our common European problem. Whether we like it or not: we are bound together. Romanian society has a unique commitment to corruption-free politics and this needs European support.

The veto, on the other hand, is hurting the people, not the criminals. While several central European countries show a growing indifference to corruption, it would be wrong to punish a society that does not think that way and still resists.

“Imagine cancelling your tax residence from the country where your head is on the coins”, the tweet says.

In Spain, corruption has reached the highest level: the monarchy. After decades of a policy of eyes wide shut to the shady business of Juan Carlos I (our first King after the Franco dictatorship), the scandal grew so big that he was forced to abdicate to save the institution.

So now, as “emeritus King” Juan Carlos lives in “exile” in the United Arab Emirates, where he had previously used his status as the Spanish monarch to make business.

Juan Carlos has even changed his tax residency to the UAE to avoid investigation by the Spanish Treasury for tax evasion regarding juicy ‘presents’ from his Arab friends. Surreal, isn’t it? So much that the Spanish can only do one thing: laugh.

Ten years ago, it seemed hopeless. Corruption in Ukraine was so ubiquitous it was hard to name a sector that bribery and sleaze did not infect. Education, customs, medicine ― at every level of society was a corrupt method of getting things done, which was the easier route for many citizens.

Then-president Victor Yanukovych headed the trend, amassing a treasure trove of bribes. The 2013-14 clashes started partly because people were fed up with corruption. New president, Petro Poroshenko, won using the slogan: “Living in a new way”.

At first, everything went according to plan. Comically clumsy, pot-bellied bribe-takers from the transport police were fired, and new staff replaced them. After training, the officers worked according to western standards. Even well-paid managers or lawyers joined the traffic cops.

With transport police it was ― and is ― a success. But high-profile corruption remained: people like oligarch Dmytro Firtash were forced to leave the country, but kept their wealth. Five years ago, society radiated disappointment. New president Volodymyr Zelensky won a landslide with the promise: “As spring comes, we’ll start putting corrupt people in jail.”

Yet again nothing happened. Firstly, the pandemic messed up his plans, then Russia invaded. Ukraine had even bigger challenges ― until the war caused the biggest anti-corruption shift ever.

Without financial help from the West, Ukraine can’t make ends meet ― and our allies have set the rules for access to cash. One of these rules is reliability. That’s why our anti-corruption bodies are finally working at their full capacity.

Last week, in a true crackdown on the Ukrainian corrupt officials, investigators ordered hundreds of searches, and many suspects were detained. Several regional governors lost their posts, as well as customs and tax service management.

In a strange situation where war and hardship push Ukraine towards the rule of law, our only hope is that the effect will be long-lasting.

Thanks for reading the 18th edition of European Focus,

This week’s newsletter was brought to you from a country that is now perceived as having the worst public sector corruption record in the EU, according to Transparency International.

The spokesperson of the Hungarian government blames “questionable methodology’ and shady background funding, while – sadly – he did not try to find an explanation to the low ranking, let alone a solution.

If you have any ideas, send us your thoughts and comments on the topic to info@europeanfocus.eu.

See you next Wednesday!

Viktória Serdült