Hi from Kyiv,

Neither me nor my parents and grandparents witnessed the Second World War. Yet, of all the past conflicts our country has endured, this one influences our lives the most.

What we choose to highlight about WWII shows our vision of history, and our political and human values. How should we name the period? ― The Second World War or The Great Patriotic War? Was the Soviet regime a liberator, or the same evil as the Nazi state? Do we commemorate the end of the war by celebrating the victory, or as a day of mourning for all the pain it has caused? These questions have sparked debates in Ukraine for many years.

My country is not an exception. WWII caused the largest mass protest in modern Estonian history, and it is the reason for erecting controversial monuments in modern Hungary and maintaining Soviet memorials in Germany. In Italy, empathy towards some fascist participants in the bloody conflict even reaches the highest echelons of the country’s leadership.

Almost 80 years after its end, this war still brings challenges to European societies. With another war continuing to rage, this debate has become even more intense. The ninth of May is a day with many faces, and many meanings for people, and we highlight some of them below.

Anton Semyzhenko, this week’s Editor-in-Chief

Windows broken, stores looted, wrecked streets and a nation in shock. This is what I saw on my way to a secondary school civics exam, scheduled for the morning of 27 April, 2007.

It was hard to revise the evening before because I was experiencing a different kind of civics exam – watching the events of Estonia’s now-infamous Bronze Night (Pronksiöö) play out on TV.

This was centred around the Government’s intention to relocate a monument for a Soviet soldier from the so-called Great Patriotic War. The difference between that concept and the Second World War? The latter began in September 1939 when both the Nazis and the Red Army invaded Poland, and each occupied half of the country. The former began only in 1941 when the Nazis turned on their Soviet allies.

The Bronze Soldier had become a flashpoint of division between two concepts of history. After another round of provocations, riots broke out in central Tallinn. This kind of unrest had been unknown in a peaceful country that had just joined the EU and NATO. Born in 1988, I had felt I was living at the end of history.

Due to the riots of mostly Russian-speakers and with another Great Patriotic War anniversary imminent on 9 May (the Victory Day of the Soviet Union over the Nazis), the Estonian government relocated the monument that very night in 2007. 16 years later, officials are still trying to distract attention by focusing on Europe Day – the celebration of the European community, which happens on the same day. This year, a free concert was held on Freedom Square featuring Kalush Orchestra, Ukraine’s winners of Eurovision last year.

People showed up at the concert to support Ukraine and a free Europe, but the wounds of Estonia’s social fabric have not fully healed. Many ignored the concert, and opted to lay flowers at the foot of the Bronze Soldier. The battle between histories continues.

In Berlin, we have four Soviet war memorials. The biggest includes a huge statue of a soldier and several stone coffins inscribed with gilded quotations by Joseph Stalin.

According to the 1990s agreement on German unification, the German state must maintain these war memorials. In the early 2000s, even the Stalin quotes were regilded.

Every year, people come here to commemorate the defeat of Nazism, including leftists and visitors bearing Russian nationalist iconography. Because of the Russian war against Ukraine, the police have tried to ban Soviet, Russian and Ukrainian flags from being flown on these Soviet memorials on 8 and 9 May.

However, a court decision has exempted Ukrainian flags from the ban.

For Ukrainian schoolchildren of the 2000s, 9 May meant visits to the local parade, where they handed flowers to war veterans, who marched down the main street. The kids wore a small black and orange-striped St. George ribbon ― a symbol of “The Victory over Nazism”.

Last year, when Russians occupied part of the Kharkiv region, a villager volunteered to work with the occupiers, while wearing the ribbon of Saint George. When Ukrainian forces liberated the village, the local residents turned on him, and this once-important symbol. He was then detained by police.

How did this change happen?

On 9 May in 2010, Russia renewed the lease on its Russian naval base in Ukraine’s Crimea region, and a full-scale military parade with Soviet symbols took place in Kyiv.

In 2014, the Russo-Ukrainian war began. People sympathetic to Russia started wearing the St. George ribbon. A year later, Ukraine adopted decommunisation laws, which banned Soviet symbols, alongside Nazi imagery. The main holiday became the 8 May as the day for remembrance and reconciliation, and a red poppy became its symbol. Ukraine stopped holding military parades in May ― and Russia started organising them in the occupied territories. Russian President Vladimir Putin even visited such a parade in Sevastopol, Crimea, in 2014.

Despite this state policy, 80% of Ukrainians still considered 9 May an important day. But that was before Russia invaded further. The full-scale invasion changed this attitude: now only 15% of Ukrainians have this view.

A year ago, Ukrainians were leaving large cities, concerned that Russia may use nuclear weapons on its Victory Day of 9 May.

Now, people in Ukraine are discussing whether they’ll sleep at all, as Russian attacks are especially intense.

In the past, the only explosions we heard on these days were fireworks. Today it is missiles. There is no atmosphere of celebration, only the feeling of danger ― and the need for truth.

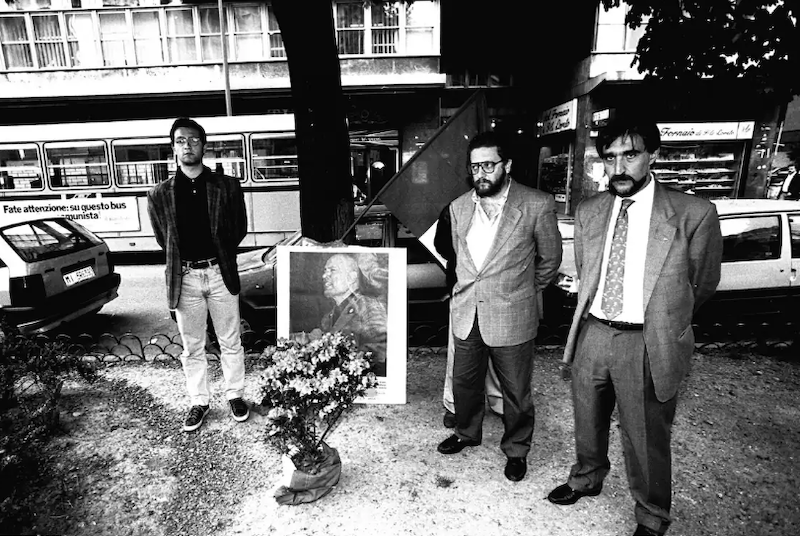

“The Partisan attack in Via Rasella was a page in the history of the resistance that was anything but noble. Those who were killed were a music band made up of semi-pensioners, not SS Nazis.”

This is a quote from Ignazio La Russa, Italy’s President of the Senate. Before being promoted to the second-highest ranking role of the Republic, La Russa was well known for his fascist roots. Not only did he collect Benito Mussolini’s memorabilia, but he also started his political career as leader of neofascist Youth Front.

La Russa was a co-founder of Brothers of Italy, Giorgia Meloni’s party. As soon as the far-right coalition won a majority, Meloni gave him a promotion. As a result, the president of the Senate is revising history. On 25 April, Italy’s Liberation Day, he didn’t join the President in a visit to anti-Fascist memorial in Piedmont, opting instead for a trip to Prague.

Art historian András Rényi on the tough conversation about WWII memory in Hungary.

The Hungarian state and society is shirking its responsibility for the Holocaust – this is one of the most frequent criticisms of the memorial to the Victims of the German occupation, erected in Budapest in 2014.

This disapproval of a memorial which makes no mention of Hungary’s role in one of the 20th century’s darkest chapters has even developed into a grassroots protest. For almost ten years, civil members of the Living Memorial movement have regularly gathered near the memorial to talk about their memories, such as the role of Hungarian authorities in the holocaust, and family deportations and mass killings.

András Rényi talks about this initiative.

How does this debate affect the memory of the Second World War?

Symbolic politics is one of the most important playing fields of the Hungarian regime of today. Under the current constitution, Hungary was not sovereign for 46 years due to the German and Soviet occupations, and everything that happened during this period was down to collaborators.

In the controversial statue, a German eagle swoops down on the Archangel Gabriel, who drops the orb (part of the Hungarian crown jewels) from his hand. The same Archangel leads the conquering Hungarians towards the Carpathian Basin on the monument in Heroes’ Square.

These two works of art in Budapest mark the beginning and the end of Hungary’s thousand years of history, and the beginning of a new Viktor Orbán era, which takes no responsibility for the sins of the past.

Has it been possible to counterbalance this message?

The Living Memorial movement is one of the few initiatives that forced the Orbán government to a symbolic defeat. The occupation memorial – which attracted such criticism – has never been officially inaugurated.

What is the status of the memory of the Second World War today?

The knowledge and experience accumulated during the Second World War becomes more and more distant and impersonal. And now it is being reactivated, because of Russia’s war against Ukraine. The images of the massacre in Bucha shocked the whole European public, for example. Putin’s aggression has reinforced the sense of danger in the liberal world.

Thanks for reading the 29th edition of European Focus,

For two decades after the victory over the Nazis, there were no large celebrations in the Soviet Union. No parades, no concerts ― mostly mourning and reflecting. As the memories faded, the state used WWII as a form of propaganda. The cult of victory grew stronger and politicians still use this for their purposes.

Now we are going through another war, how will we treat our memories of this conflict in the future?

See you next Wednesday!

Anton Semyzhenko