Hi from Tallinn,

My country has never played at the World Cup or won a major sports competition, but for several months, we have topped the EU inflation chart (22.5%). Rising costs could force the sick and elderly out of care homes. I can lament over this situation for only so long, until I realise how much worse things can get.

In Moldova, inflation is at 35% and wages are about three times lower than in Estonia. For Moldovans, everyday struggles are exacerbated by energy blackmail from Russia, and actual missiles landing in their backyards. I found all of this difficult to comprehend considering the supposedly dire situation in my own country.

Governments are scrambling to come up with solutions – all of them are imperfect, but a lot are also unfair and infuriating to people who have worked hard their entire lives. This week’s edition will offer some lessons on what to avoid.

Herman Kelomees, this week’s Editor-in-Chief

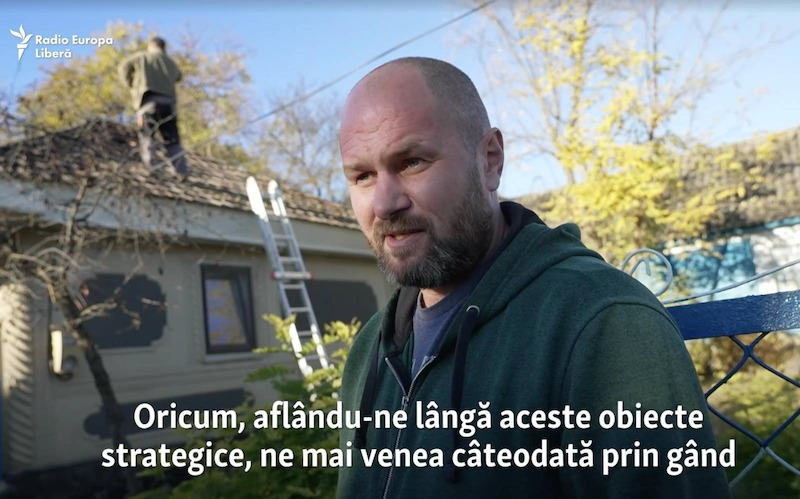

Andrei Luca was teaching history when he heard the explosion of the first Russian missile that fell on the territory of Moldova. The sound of the muffled boom came from 6 km away, from Naslavcea, the village on the country’s northern border with Ukraine.

“In half an hour, the scared neighbors called me to tell me that the shock wave broke their windows, and some pieces of the ceramic tile on the roof of my house.”

Although this was the first direct damage from the war that has spilled over to Moldova, it was not the first severe blow to the country. Having half of the energy infrastructure in Ukraine destroyed by the war forced Kyiv to stop exporting energy, and Moldova had to look for alternatives for energy supply.

All of this is happening in a country with a 35% inflation rate (the highest in Europe other than Turkey) and an average salary of only a bit more than 500 euros. Inflation hits the elderly even harder: the state minimum pension is 100 Euros per month, but the monthly food basket is 120 euros.

This is because the separatist, Kremlin-backed Transnistria region decided to drastically cut its supply to Moldova. It used to supply 70%of Moldova’s energy, now it will provide only 27%.

After the bomb attack, Andrei had to spend 270 euros out of his pocket for bills, mostly for heating, now powered by electricity from Romania, which is three times more expensive. “This month we’re switching to wood and coal,” he says.

In order to ensure the bare minimum for his three small children, he does extra lessons, rents an apartment in the capital and works as a pastor at two evangelical churches on weekends. “We can’t afford to live on our salary alone,” he says.

“Invitation to governmental press conference at 22:30. Please register by 22:00 today” – such emails are not uncommon for journalists. But when Hungarian newsrooms received the above invitation last Monday, it was already 21:46.

Having only 10 minutes to register and 45 minutes to reach the ministry in the middle of the night was new even by the standards of the Orbán government, which has made a habit of announcing bad news at the very last minute.

This time, it was the scrapping of the fuel prices cap, but from the abolishment of taxes to the raising of household utility prices, Hungarians often have only a day, or even minutes to prepare. No wonder Gergely Gulyás, head of the Prime Minister’s office, who holds weekly press conferences, is the subject of numerous jibes.

While Hungarians know laughter is the best medicine, this time they are wondering how long till the joke wears thin?

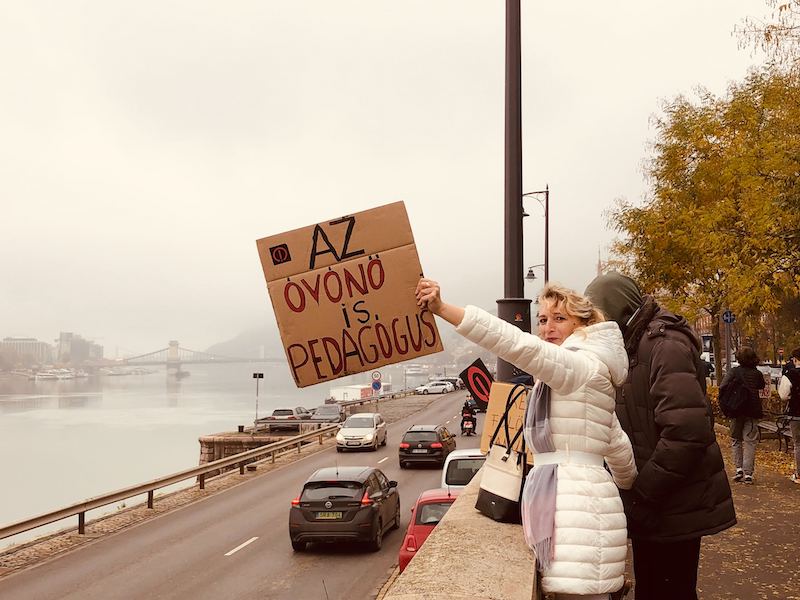

Last month in Budapest I was struck by a human chain of teachers protesting sneaky ways to hit the education system. Viktor Orbán’s government keeps their salaries very low. A young Hungarian teacher earns less than 500 euros a month, while inflation has hit 22.5%.

A British teacher makes around six times more than a Hungarian counterpart, but the tune is the same: I also came across strikes in Edinburgh. UK teachers rejected a five per cent pay increase: given inflation there is 11 per cent, “these are cuts”, their union said.

And that’s the point. While the cost of living rises, governments do neglect school and health, our most valuable collective goods and investments. We have seen welfare under attack during the financial crisis. Then we had the pandemic; Italy was the epicentre. But we didn’t learn the lesson: public health continues to be mistreated.

When Giorgia Meloni’s government launched the budget bill, doctors sounded the alarm. Funds are even more inadequate if you consider inflation; of two billion euros, 1.4 billion will be used to pay for the rise of energy bills in health facilities. Italian doctors predict the exodus of a third of them from the public health system.

Do we want our life-saving doctors and our passionate teachers to suffer humiliation? Leaving their jobs for being worn out? I do not. I want to give them a voice with our Focus: their stories concern us as Europeans. Are we repeating the same pattern with this crisis? Will governments dump costs on the weakest and let our welfare and our collectivity pay?

As the poet Audre Lorde wrote, “when we speak we are afraid our words will not be heard, nor welcomed but when we are silent we are still afraid. So it is better to speak.”

22.5% is the inflation rate in Estonia in October, this is the highest value in the Eurozone, compared to 10.6% in the euro area overall.

While it’s possible to cut back on some costs, there are some expenses that people have to accept. Nursing homes in Estonia are increasing their prices. “I cannot pay [an additional 300 euros] for that,” stated Kristel, to daily newspaper Eesti Päevaleht.

Estonia’s local governments will start to compensate for some of the nursing care costs, but not until July. As pensions only cover a part of these fees, people with relatives in the nursing homes might have to take out loans or work in second jobs to cope.

While purchasing power plummets throughout Europe, in Belgium wages continue to rise. This is because the salaries of civil servants and private sector workers are indexed to inflation. The same applies to pensions and social welfare. Every 1 January or four to five times a year, depending on the industry or sector, salaries increase according to the “smoothed health index”. Its calculation is slightly different from inflation, as it does not take into account the price of alcohol, tobacco or petrol.

The indexation of wages to inflation was introduced gradually at the beginning of the 20th century. It has survived the changes in the labour market, globalisation and the oil shocks which led Belgium’s neighbours to abandon similar systems. Today, Belgium is the only country in Europe, along with Luxembourg, to benefit from such a scheme.

During each economic crisis, the same debate resurfaces: should this mechanism be modified? Belgian employers are regularly calling for a freeze in automatic indexation, arguing that the policy puts them at a disadvantage versus their neighbours.

Today, with inflation reaching over 12%, the highest rate since 1975, employers’ unions want to establish an income ceiling above which indexation would be reduced or abolished. On the other hand, 73% of Belgians believe that the mechanism is insufficient, due to the explosion in energy prices, according to a survey in Le Soir newspaper.

However, the results are visible. According to forecasts by the Bank of Belgium, the purchasing power of Belgians should increase by 0.3% in 2022. This compares to a fall of 6.8% in the neighbouring Netherlands.

Thank you for reading our 12th issue of European Focus,

It is going to be a difficult winter. I hope this week’s edition has helped to offer you some ideas on what kind of solutions from around Europe work and which do not. It is as important to consider what’s fair and what we must demand from our governments.

Feel free to write to us with your opinions and suggestions, and we hope you have the chance to prepare for the holidays!

See you next Wednesday!

Herman Kelomees