Hi from Berlin,

and welcome to the last issue of this year, the last issue before the winter holidays. Are you celebrating something? And if so, what? Without having actively asked, I know that at least two members of our European Focus team are not celebrating Christmas. For others, it appears to be the most wonderful time of the year.

Is it necessary for societies to share religious celebrations? What if some members don’t? The question of how and in what way religious festivities should be publicly visible has been the subject of political struggles in recent years. Although one can also imagine a society where opening up to diverse religions’ celebrations can be enriching for everyone, as our colleague from the UK reveals to us.

In the end, the question may be: how can we find a common ground in our societies? Religious celebrations should be a source of joy, strength and happiness to those who celebrate them, but to celebrate or not to celebrate must always be an individual decision.

Teresa Roelcke

this week’s Editor-in-Chief

Can you imagine a nativity scene without Mary, without Joseph, and without even Baby Jesus? That is what is happening in the small town of Beaucaire – because the mayor wants to circumvent a 100-year-old French secularisation law.

This prohibits the installation of religious symbols, such as a newborn in a manger, in public buildings, in order to keep public service neutral. After having been convicted on several occasions, the municipality decided this year to keep the nativity scene inside the town hall, but without its main characters.

“They sue us three or four times a year for this beautiful cultural exhibition. What sense of priorities do these people have?” complained the mayor. These ‘people’ are, in fact, the prefecture, the representative of the French state, who regularly takes the municipality of Beaucaire to court for not respecting secularism.

Since their election less than ten years ago, a new wave of far-right mayors has decided to turn nativity scenes into a battlefield, by installing them in their town halls. In their eyes, it is not a religious symbol but a cultural tradition.

Their vision of secularism is also very flexible. They are its most ardent defenders of neutrality when it comes to prohibiting the construction of a mosque, yet they do not hesitate to violate it when it comes to Christian tradition.

Robert Ménard, the mayor of Béziers who started the trend of nativity scenes in town halls, was not only convicted of not respecting secularism. He was also found guilty of ‘provocation to hatred’ in 2017 for saying that there were too many Muslim children in his town’s schools.

This obsession with nativity scenes does not stem from a simple love of the Christmas spirit, as some far-right mayors would have us believe. It is part of a xenophobic and Islamophobic political agenda.

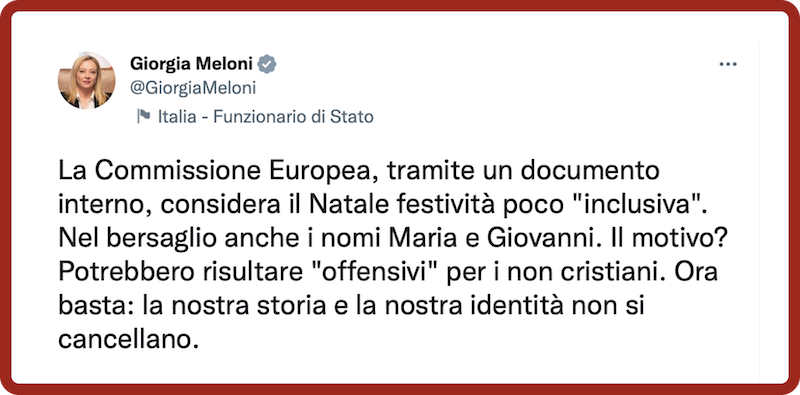

The European Union has never tried to cancel Christmas. This was a piece of fake news spread by the Italian right wing. In the name of tradition and propaganda, Giorgia Meloni led a crusade against Ursula von der Leyen.

This happened last winter, when the leader of Fratelli d’Italia wasn’t yet Italy’s prime minister. “That’s enough!” she wrote in a tweet, addressing the president of the EU Commission. “Our history and identity cannot be erased!”

Did the German Christian-democrat want to profane Christmas? No. Brussels never tried to “erase Christmas”.

The European Commission drafted some internal ‘Guidelines for Inclusive Communication’ suggesting that officials should “avoid assuming that everyone is Christian. Not everyone celebrates the Christian holidays. Be sensitive about the fact that people have different religious traditions and calendars: ‘holiday times’ would be preferable to ‘Christmas time’.”

All the noise had an effect: after the Italian right launched its campaign against “political correctness”, the Commission withdrew the document.

Lorenz Blumenthaler is press officer for the Amadeu Antonio Foundation, which combats right-wing extremism, racism and anti-Semitism in Germany.

European Focus: In recent years, a debate has raged in Germany over the naming of some markets that open during the festive period ‘winter markets’. Why are these Christmas markets, which are hardly a religious symbol, igniting a heated discussion?

Lorenz Blumenthaler: There is a right-wing narrative that is reheated every year claiming a “war on Christmas” that is allegedly driven by a supposed “Islamisation” of the west. This is reflected in the renaming, abolition, or replacement of common “traditions” which then represent gestures of submission to this “Islamisation.” However, this is an anti-Muslim conspiracy narrative that is mainly used to stir up fear of Muslims in Germany.

EF: Where did this narrative arise from?

The origin can be traced back to the U.S. In the early 20th century, car magnate Henry Ford circulated anti-semitic publications claiming that Christmas traditions were being restricted by Jews. The modern debate was largely driven by the American alt-right. Since 2004 Fox News anchor Bill O’Reilly pushed this and also U.S. President Donald Trump took up the narrative during his 2015 campaign.

The “war on Christmas” fell on fertile ground within the German right. Every year, members of the far-right AfD party, in particular, try to scandalise alleged renaming campaigns. In their eyes Germany is lost when discounters sell “Winter decorations” instead of “Christmas decorations”. If taken seriously, one gets the impression that the self-declared “Christian-Jewish Occident” is defended above all on the front of Advent Calendars. The only goal of these fabricated agitations is to stir up sentiment against Muslims.

EF: The discussion around the alleged “war on Christmas” was not prominent this year. Why?

Inflation, a global pandemic, a Russian war of aggression, the energy crisis, and refugees from Ukraine – who needs a “war on Christmas” when you have all this? Probably these crises and issues offered a sufficient enough basis to spread hostile and racist ideology.

North Macedonia is blessed with beautiful Orthodox Churches and Mosques. But sometimes, religion in this secular country can become too intrusive on the public space.

A 66-metre-high Orthodox cross overlooks the capital Skopje. Built in 2002 to mark two millennia of Christianity, this cross instils a sense of pride in some, but for others it is a prime example of megalomania, including for many Muslims who live in Skopje.

The second largest religion, Islam, has also drawn criticism. People have complained about the noise coming from the mosques’ loudspeakers. I measured a staggering 80 decibels during the afternoon prayer in Skopje’s Cair municipality. The legal limit is only 45 decibels of noise.

“I have a message for Liz Truss… We work hard. We work the longest hours in Europe,” the Trade Union Congress (TUC)’s General Secretary Frances O’Grady told her conference in October, referring to the former UK prime minister’s leaked audio comment that British workers needed more ‘graft’.

British workers have fewer public holidays (known as bank holidays, as these were initially exclusive to bank workers) compared to their European peers.

O’Grady and other union leaders have called for new bank holidays to reward British workers and this, paired up with data from the 2021 census of the Office for National Statistics, which highlights the UK’s diversity in terms of ethnicity and religion, creates an opportunity.

Given the UK’s rich melting pot, workers of all confessions should have the same opportunity to celebrate their religious holidays with their families, from Ramadan to Diwali, from Hanukkah to Vaisakhi, as Christians celebrate theirs.

As all British workers, religious and nonreligious, need more holidays, these times could be used to learn more about different communities in Britain, as happens during Black History Month.

Another element that could reinforce a similar scenario is the role of the monarchy, as King Charles III inherited the Queen’s role as head of the Church of England, but at the same time, he labelled himself as “Defender of faiths” back in 1994 and will recognise all faiths during his coronation in May 2023.

At a time when divisions run deep and social tensions are rising, the opportunity for holidays where all Britons rest and spend time with their families, while exchanging and learning about other communities, would pay tribute to the kaleidoscope of cultures, religions, and traditions that represent the United Kingdom today.

Thank you for reading our 13th issue of European Focus,

and for wandering with us through the sensitive territories of a holiday torn between political struggles. To those of you who do celebrate, we wish a joyful and warming Christmas. To those who don’t, we hope that you can enjoy a happy and reinvigorating vacation. And to all, we wish a peaceful, happy and healthy New Year.

See you again on 11 January!

Teresa Roelcke