Hi from Târgu Mureș/Marosvásárhely,

A few years ago, nine passengers died in a car accident not far from my home. A poorly equipped minibus full of Romanian migrant workers crashed. The victims had previously worked hard for low wages in harsh conditions, and for what? They left 16 children orphaned. This is one of many migrant worker tragedies in my immediate vicinity.

Another story is about two Sri Lankan migrant workers. The bakers came to Romania in the hope of a better life. They wanted to make bread for the people here. A peaceful plan, wasn’t it? They were attacked by locals whose family members have also worked as migrant workers in central and western Europe. Xenophobia, racism and social unrest flared up immediately.

European societies struggling with anti-migrant sentiments don’t seem to recognise their own interests. Our new edition this week tries to highlight these contradictions.

Boróka Parászka, this week’s Editor-in-Chief

Two years ago, I met Andrei Amariei*, a young Romanian who had been working in the German meat industry. At that time, the pandemic was wreaking havoc in Europe, and the role of essential workers across Europe was making headlines.

Andrei told me about 12 hour-shifts in freezing temperatures, long weeks without a day off, and a salary the bosses often slashed with no justification. “Germans see the Romanians as three or four classes below them, as the lowest in Europe,” he summed up.

Andrei is one of millions of Romanians trying to earn a living in western Europe, many of whom face discrimination and slave-like conditions.

In their absence, the Romanian economy struggles to find replacements. In 2022, the government allowed companies to hire 100,000 non-EU workers – the largest number ever authorised. Most of them come from Nepal, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, India, Pakistan or Vietnam. I see them working in fast food restaurants and on construction sites, crossing Bucharest on bikes to deliver food, or in their free time, trying to make sense of this messy and confusing east European city.

Their experience is similar to that of millions of Romanians abroad since the Revolution. In 2020, residents of a village in central Romania rioted after a local bakery hired two workers from Sri Lanka. The story inspired award-winning director Cristian Mungiu’s latest movie, R.M.N.

A current investigation described the conditions of many foreign workers in Romania: they work up to 60 hours a week, sometimes without a contract, and live in overcrowded containers.

In the absence of policies to improve the European labour market and build solidarity in a world where profit dictates all, a chain of abuses is linking the West and the East. The exploited soon becomes the exploiter, and the weakest will suffer, as they always do.

*The name was changed, as the worker feared a legal dispute with his former employer.

2.2 million Poles lived and worked abroad for more than three months during the last year. In parallel, the number of Ukrainian workers is rising in Poland, many replacing the missing Polish labour force.

Even before the war, Ukrainians came to Poland in large numbers in search of work. Last year there were 1.5 million. After the Russian invasion this number more than doubled.

Ukrainian workers have become crucial to the Polish economy, which continues to grow, despite skyrocketing inflation.

Ukrainians coming to Poland are first hired for the lowest-paid jobs, like the Poles when they arrived in west European countries.

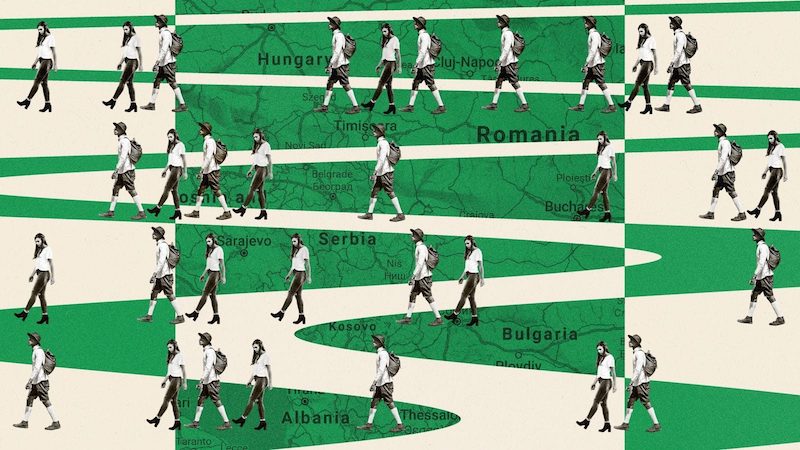

Young people are leaving. The population is ageing, and birth rates are declining. There is a chronic lack of workers, as they have been vacuumed out from the region – this is the gloomy picture of the Balkans today.

No wonder few want to stay. With wages a fraction of the EU average, the region is still entangled in border disputes, ethnic quarrels, rampant corruption, unfinished EU and NATO accession (in some states) and the ghosts of the wars of the 1990s.

“People see no future here, so they seek their fortunes in central and western Europe or anywhere else. It’s not only about the money, but above all about the comparatively lower quality of life [at home],” says Ilija Aceski, a professor of sociology in Skopje.

If one believes the projections of the United Nations, the World Bank and the statistical agencies, Bulgaria will have 38% fewer people in 2050 than in 1990. In Serbia, numbers will be down 24%, and North Macedonia and Croatia will see a 22% drop.

Unlike in Germany, France, Poland or even Romania, there is no influx of migrant workers to fill the vacancies. Despite the millions of migrants and refugees from the Middle East who have passed through the region in the last decade, almost no one wanted to stay. Just like the inhabitants of the Balkans, they dream of a life in wealthier countries.

Both the public and private sectors are hit. Everywhere you look, there is a chronic lack of doctors and nurses. The same goes for engineers, plumbers, bricklayers and other skilled professionals.

“It’s a vicious circle,” adds Aceski. “The more people leave, the more the overall quality of life dwindles. And that in turn causes even more people to flee.”

In his opinion, governments have so far offered very few resources and sound plans to stop the exodus.

“It is absolutely necessary to regularise workers who make this country work and who are, unfortunately, in an irregular situation”

For Laurent Berger, general secretary of CFDT, one of the main French workers’ unions, the French government’s recent proposal for the immigration law reform, which will be discussed in Parliament at the beginning of 2023, doesn’t go far enough.

One of the suggestions is to ease the professional integration of foreign workers by delivering a residence permit for “jobs in tension”, in sectors where it is difficult to fill the vacancies, such as in hospitality and construction.

In an interview for French television France 2, Laurent Berger suggests that the immigration situation requires an approach “not only economically useful, but also socially thankful to these workers”. He argues that they need to be “automatically regularised” and provided with work permits and official papers.

Things are finally moving. The German government of the Social Democrats, Greens and Liberals is planning to liberalise the immigration law: naturalisation should be possible earlier and foreign professionals should be able to find a job in Germany more easily in the future.

This change would recognise that Germany is an immigration country. It has been for decades. The strength of Germany’s post-war economy would never have been possible without the “Gastarbeiter” (“guest workers”) recruited in the 1960s.

Acknowledging that Germany is an immigration country immediately calls on those who have nurtured their racism for years and have campaigned against more liberal immigration laws. A few days ago, a conservative politician complained that German citizenship should not be “sold off”. And the leader of the Christian Democrats said: “German citizenship is something very precious that must be handled with care.” Even within the government, the liberals are somewhat hesitant.

It is striking, however, that leading business representatives are calling for liberalisation. Germany needs immigration: about 400,000 workers per year are missing. The boomer generation will soon retire, and then their labour will be lacking.

What’s sad but true is that Germany’s prosperity is also based on some level of well-cultivated racism. How else could one comfortably justify allowing migrant workers to work under much worse conditions than their colleagues who are considered Germans? How else could one tolerate the gross violations of health protection of migrant workers in the meat industry during the pandemic? The blatant injustice of not paying workers at all on the construction site of the prestigious Mall of Berlin?

So the conflict will not be so easy to pacify. Not only because a part of German society is simply so ideologically stubborn. But also because racism has a tangible function for the interests of the German economy.

Thank you for reading our 11th issue of European Focus,

The winter holidays are coming, when we tend to focus on empowering and heart-warming stories. The European migrant workers stories summarised in this newsletter do not suit this holiday mood. Because there is never a holiday or a weekday without their efforts, it should be a common European interest to regularise fair work conditions for everyone.

Feel free to write to us with your opinions and suggestions, and we hope you have the chance to prepare for the holidays!

See you next Wednesday!

Boróka Parászka