Hi from Prague,

Can you imagine a Wolf in judge’s clothing? Or a Head of a Constitutional Court who is the governing party leader’s “social discovery” whom he “enjoys visiting”? Politics and the justice system clash in many countries. This Monday, the European Court of Justice struck down more elements of Poland’s judicial reform, ruling that publishing online declarations of judges’ memberships of foundations or political parties violates their privacy rights.

The problems in Poland, Hungary and Ukraine are widely known. Still, you may be surprised to read that in Spain, the body overseeing the country’s judicial system has been operating on an interim basis for more than four years – due to a dispute between the two main political parties. Even in Germany, there are issues between politics and justice.

Talking about the rule of law and the justice system might sound boring at first, but I’m confident you will find fascinating reading in this week’s edition of European Focus, as the challenges see parallels across borders.

Gyula Csák, this week’s Editor-in-Chief

Poland’s courts are having problems staffing incompetent judges. This is the result of the governing Law and Justice’s “reforms” since the party won an outright majority in 2015.

The epitome of these problems is Julia Przyłębska, the chairwoman of the Constitutional Court, whom Jaroslaw Kaczynski, the leader of Law and Justice, called “his social discovery”. He often met her privately and praised her culinary skills.

Przyłębska became a judge in 1987. She passed the state exam with ‘barely sufficient’, the lowest possible grade for admission to the profession. There are many similar examples. The Association of Independent Judges “Iustitia” published a report showing that the Minister of Justice, in the first years of the “reform,” replaced 160 court presidents with his appointees, despite many lacking qualifications. As a result, the waiting period for resolving cases in Polish courts has increased.

The purpose of such operations is for the governing party to gain the loyalty of judges. The Constitutional Court under Przyłębska’s leadership issued rulings in accordance with the will of the authorities. An example was in 2020, when the judges ruled that abortions previously allowed in cases of fetal damage or defects were unconstitutional. This led to huge protests.

But resistance to top-down changes imposed by the authorities is still strong in Polish courts. Ziobro’s nominee judges are being dissected by the “old” part of the judiciary, making it impossible for the former to rule smoothly.

Also, the work of the Constitutional Court is frozen. Some judges are demanding that Przyłębska leave, recognising that her term has expired. They do not want to come to court sessions. The court under her leadership has become a de facto dysfunctional institution.

The EU is the last guardian of Polish courts’ independence, and it should not hold back in its efforts to defend this key principle of the 27 member-bloc.

Is it possible to “kidnap” an entire organisation? The Spanish government accuses the opposition of seizing control of the General Council of the Judiciary (CGPJ).

The body, which oversees the judiciary in the country, has been operating on an interim basis for more than 4.5 years, or 1,643 days, as parliament cannot agree on the election of its new members.

The mandatory reelection needs a 3/5 majority in both houses of the Spanish parliament, meaning the two main parties, the governing Socialists and the Conservatives, must agree on the 20 members. Until then, members appointed from nine years ago are (mostly) staying in their posts. Such a decision might not happen before the snap elections this July.

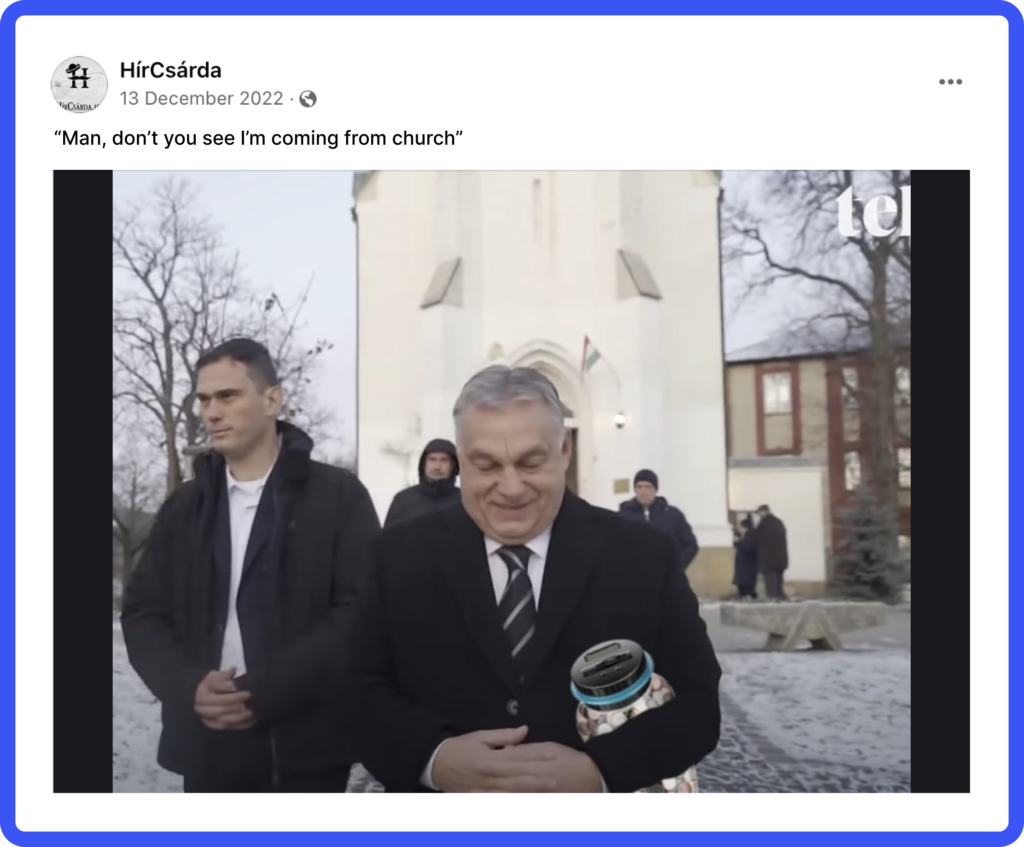

Suffering from low growth and battling the highest inflation in the European Union, Hungary is desperately in need of EU funds.

However, this cash has been suspended due to Brussels’ concerns over Hungary’s record on tackling corruption and maintaining the rule of law. So, when the Hungarian parliament adopted judicial reforms that entered into force on 1 June, there was a palpable sigh of relief.

No wonder: this package of new policies was a prerequisite for Budapest’s claim to €13.2 billion of the locked cohesion money.

Political pressure on the independence of the judiciary in Hungary has long been a domestic and international concern. A senior Budapest judge complained he and his colleagues “have been witnessing external and internal influence attempts” for years. The rule of law report of the European Commission also highlighted problems, including challenges faced by the National Judicial Council (a self-governing body of judges), rules on electing the President of the Supreme Court, and the possibility of favouritism in judicial appointments, promotions, case allocation and bonuses.

For some time, it seemed not even the Commission was paying enough attention. When the EU executive launched its budget conditionality procedure against Hungary for violations of the principles of the rule of law, they did not raise the issue of judicial independence. Only after pressure from the European Parliament, did they make this issue one of the conditions for Hungary’s access to €22 billion from the EU’s cohesion funds and to €5.8 billion from the recovery fund.

Hungary had no other choice but to address the concerns, and chose money over ruling the courts.

However, some experts and NGOs warn the Commission not to oversell these results. The judicial reforms fail to tackle the most important issues of which the Hungarian government is accused: corruption, conflict of interest and rigged public procurements. With that unchanged, the very nature of the Orbán government will remain intact, and the justice reform may quickly turn out to be just a “fig leaf” to hide the real problems with the rule of law.

“…this includes precisely the question of whether the Letzte Generation is a ‘criminal organisation.'”

Since April, climate activists, calling themselves “Letzte Generation” (“Last Generation”) have been trying to bring car traffic in Berlin “to a halt” by glueing themselves to crossroads. This has led to heated debates, and provoked a lot of hatred from car drivers towards the environmental protest. A few weeks ago, Felor Badenberg, minister of justice of the federal state of Berlin, instructed her administration to examine whether these climate activists fulfil the criteria of forming a criminal organisation. Her announcement caused uproar in the German public, especially as the prosecutor of the federal state of Berlin had already declared that he didn’t consider “Letzte Generation” a criminal organisation. Does Berlin’s minister of justice want to impose political directives on the prosecutors? If she wanted, she probably could: In Germany, prosecutors are eventually bound by directives issued by the ministries of justice, although it is not very common to use this tool.

Helping corrupt officials avoid punishment, “burying” laws, enjoying an inexplicably luxurious lifestyle on his modest state salary are just a few things of which Ukrainian judge Pavlo Vovk is suspected.

In 2010 ― at the age of only 31 ― he headed the District Administrative Court of Kyiv, an entity responsible for solving disputes with state officials and structures. This court decided whether a law adopted by the Ukrainian parliament could be put into practice, or whether a decision to ban a political party financed by Russia was legal. Vovk could influence such cases and, according to state prosecutors, he took advantage of his position.

Ukrainian anti-corruption authorities published several tapped recordings of Vovk’s conversations. They are full of phrases such as “I’m totally for any lawlessness in the Ukrainian court system” and others which imply he can act on the wishes of this or that top politician.

Pavlo Vovk admits these recordings are true. But he says the accusations are no more than an attempt at revenge. Ukrainian anti-corruption bodies are trying to influence the court, because many of the cases they started have been stuck there. When asked why, he said: “I am strong, and the court is independent.”

“Vovk” means “wolf” in Ukrainian, which was a gift for headline writers, who titled articles “Living by wolf rules” or “Wolf justice”. His court was popularly called “the justice shop”. For years, he was notorious and untouchable.

Despite all the hatred, protests and legal suspicions against him, Vovk kept his post until late 2022. Different presidents ― Victor Yanukovych, Petro Poroshenko, Volodymyr Zelenskyy ― answered questions about him and his court with vagueness and a lack of decision. He seemed to be too influential and useful. Finally, on 9 December last year, the USA imposed sanctions on Vovk “for soliciting bribes in return for interfering in judicial and other public processes”. After this, the war-torn and West-dependent Ukrainian state finally gave up Vovk ― by disbanding the court.

Now part of Vovk’s routine is attending hearings against him. These cases are also stuck in the judicial system.

Thanks for reading the 33rd edition of European Focus,

Bribery, kidnapping, plotting – these sound like subjects of a thriller. And in a sense they are. For most of us, justice and the rule of law are not a daily concern, such as inflation or housing problems, but they are just as important to our quality of life. Let’s keep that in mind.

See you next Wednesday!

Gyula Csák