Hi from Kyiv,

Do you remember the new kid at school? Often shy and weird in many ways, with a background you sometimes could not fully understand. Joining a close knit team is challenging for both newcomers and old faces: stressful and demanding for those who’ve just arrived, and requiring compromises from the others. And you can never predict the outcome: maybe that new boy will push the local basketball team to record heights? Or ruin the classroom atmosphere, bullying those who are weaker?

A seasoned teacher would tell you that the secret is in the rules: thoughtfully calibrated, they can make the new mix a success, benefiting individuals and the group as a whole. Differences can enrich a group, diversity managers would argue.

Just like a class, the EU is set to get bigger. For security and economic reasons, this is clearly needed. And it definitely will be hard.

Are the rules fine-tuned enough? How can the system prevent bullies and liars from prospering? How can everyone feel engaged? We ponder these questions in this issue, and hope the bloc can find the answers soon.

Anton Semyzhenko, this week’s Editor-in-Chief

“We are home,” reads the faded yellow cover of the newspaper I have carefully kept in a box under a shelf for the last 20 years. Its publication date – 1 May 2004 – is symbolic for two reasons: it was the day when Hungary joined the European Union, and the day when I started working as a journalist.

In fact, one of the papers I kept is the special edition of Magyar Hírlap, where I started my career as a foreign affairs reporter.

Much has changed in the 20 years since that cover was published. For one, Magyar Hírlap has been turned into a radical right-wing propaganda outlet, while Népszabadság, the other newspaper I kept, shut down under government pressure.

It is not only my profession that the government has captured, but Hungarian society as a whole.

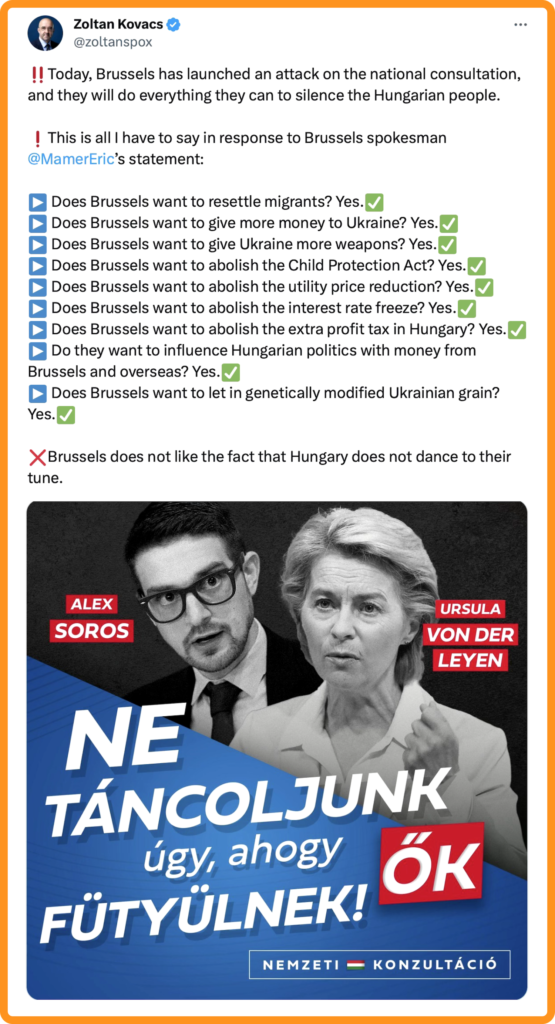

When I see official posters on the streets of Budapest, depicting ‘Brussels’ throwing bombs or the president of the European Commission as a puppet of the Soros family, I wonder if people have forgotten what it means to be part of the EU.

Government propaganda is having an impact, as support for the EU in Hungary has fallen by 10 per cent in recent years.

Still, the cover story of two decades ago was not wrong: joining the EU felt like a homecoming for most Hungarians. For us, enlargement was not only about free travel and more chances of a job abroad, but also about finding our place as a nation on this borderland between East and West. Of course, membership came with its own obligations, which both sides had to respect. But I also firmly believe that disagreement on some issues, be it migration, agriculture or foreign policy is good for the European community.

And waging war against where we have always belonged is not.

In 2005, the French rejected the adoption of the European Constitution, with a 54.6 percent No vote. The referendum was supposed to be a foregone conclusion. The right and the left campaigned for a Yes vote ― only the nationalist far right and the radical left were opposed.

One figure derailed the campaign: “The Polish plumber”.

A year after the largest enlargement of the EU, sovereigntists constantly used this expression to inflame fears of immigration by eastern Europeans who would work for lower wages. This was one of the main factors in the No vote. Yet foreign workers had nothing to do with the European Constitution. No wave of Polish plumbers or Latvian bricklayers ever arrived in France.

Now, in light of another possible EU enlargement, politicians and the public in different member countries are expressing fears that workers and goods from future EU members may flood local markets. Just like in France, some of these fears may never come true.

In last December’s EU summit in Brussels, Germany’s Olaf Scholz pulled a fast one. After a brain-numbing debate on Ukraine’s accession talks, he invited Hungary’s Viktor Orbán to grab a coffee. As soon as he left, the other member states voted for Ukraine’s EU accession to proceed.

Many in North Macedonia were flabbergasted.

Could no one have offered a freddo espresso to the Greek PM and the Bulgarian leader, in order to unblock their countries’ intransigence at granting North Macedonia the start of EU accession talks for almost three decades?

We have been stuck since 2005 in candidate country status. The Greek Euro-Atlantic blockade precedes even that, and dates back to the early 1990s.

Athens prevented Skopje’s aspirations for twenty years over what many have described as an ‘irrational’ name dispute.

Sofia now keeps both Albania and North Macedonia at bay, in an even more illogical dispute based on history, language and identity issues, in which Sofia claims that Macedonian is a Bulgarian dialect and the roots of the Macedonian people are Bulgarian.

“The EU allows its members to use their place in the bloc as leverage against their neighbours. It is the most anti-European thing one can imagine,” said Albanian PM Edi Rama at the Munich Security Conference, frustrated that his country, which is partnered-up with North Macedonia, is also blocked from launching EU accession talks.

In light of Putin’s aggression, in which Hungary blatantly misused its right to veto, embarrassing and blocking Brussels from action, a group of nine countries last year declared they want to ditch the veto from foreign policy decision making. Germany and France were among them.

They argue the veto rule has forced weak compromises and made the EU ineffective on the global stage.

Western Balkan candidates, who have been left to suffer instability, corruption, populism and foreign influences, have no reason to celebrate.

While the way out of unanimity lies within the EU acts in the form of qualified majority, there is a catch 22. In order to allow non-unanimity, Brussels would need, you guessed it ― unanimity.

Meanwhile, Scholz’s coffee trick can only work once.

“We will open the Rule of Law Reports to those accession countries who get up to speed even faster. This will place them on an equal footing with Member States”

Ursula von der Leyen

In her last State of the Union speech, the EU Commission president touched on the issues of enlargement and democracy. The subject is far from marginal: at present the EU is failing to enforce the rule of law even among its member states.

Von der Leyen, who is seeking a second term in office, has played a part in this unsuitability. She waited after the Hungarian elections in April 2022, before triggering the “conditionality mechanism”, a leverage that makes the disbursement of EU funds conditional on compliance with the rule of law. More recently, von der Leyen unfroze ten billion euro for Viktor Orbán on the eve of a European Council summit, as if values could be negotiable.

If the EU wants to keep a balance between opening borders and empowering democratic values, it should start by enforcing the rule of law inside its own bloc.

Estonia’s prime minister Kaja Kallas warns that some reforms Ukraine must initiate to join the EU will be unpopular at home.

Where would Estonia be now, if we had not had the chance or readiness to join the EU?

We would be in quite a different place. Firstly, our well-being would not be the same. Since the 1990s, our pensions have risen 65 times and salaries 35 times. The other dimension is security. Membership has an effect – as a member of this club, each one of us is not alone. We meet with other leaders so often that we become friends.

What are the fears among EU leaders about the accession of Ukraine or the western Balkan countries?

Years ago I talked with Portugal’s now-prime minister António Costa, who remembered that when their accession was on the agenda, there was a fear [among existing member states] of the “Portuguese plumber”. When we joined, the fear was the “Polish plumber” and now it is the “Ukrainian plumber”. This has not been the case because economic convergence will raise living standards and there will not be a need for large-scale migration.

There is of course the fear of corruption. Will the [prospective member states] be able to carry out reforms? In the case of the western Balkans, there is also the issue of crime. Another fear is what we see in Hungary today. We wrestle with them a lot. If so many new countries join, what will that mean for EU decision-making?

How should politicians in these countries calibrate the hopes of their people? Some leaders of future member states claim they could be ready in two years’ time.

Our accession took eight years. It requires tough reforms, which are unpopular. And they require an understanding among the people that these need to be done for the sake of a better future. We know from our experience that this will not be easy.

Thanks for reading the 63rd edition of European Focus,

For now, this is our last issue. We will hopefully be back in autumn, with new funds and fresh ideas.

The European Focus team has been working together for the past two years. During that time, and especially since we first published this newsletter in September 2022, we have worked closely together every week to step out of our national bubbles and discuss our common issues, fulfilling our ambitions set out in our first edition.

During the 18 months of production, nearly 80 journalists from 23 countries contributed to the pan-European dialogue.

We had our differences, sometimes people were busy and it was far from easy to organise a weekly production routine across five countries. But we also learned that we have much more in common than we thought.

Working together, although sometimes stressful, is always fun. We had many “aha” moments. Differences make us stronger and bring us together. Most importantly, we began to talk about “us” instead of “them”.

Because we are all in it together.Gyula Csák, Boróka Parászka and Judith Fiebelkorn, editorial coordinators of European Focus